Babylon OpenJDK: A Guide for Beginners and Comparison with TornadoVM

Published:

Introduction

Babylon is a new OpenJDK project which aims to enhance code reflection for the Java platform allowing not only to inspect classes and fields, but also to inspect methods and lambdas with the end goal of performing code transformation without using any 3rd party libraries.

What does this mean in practice? The enhanced code reflection can be used to represent different types of computation, such as for automatic differentiation [2], LINQ expressions [3] and even GPU offloading, which is the focus on this article. We are going to walk through how Babylon helps developers to define a parallel framework for GPU programming within Java, and how it differs from current solutions, such as TornadoVM.

But before we dive into the GPU workflow within Babylon, let’s define a key term, the code model. In the context of Babylon, a code model is a representation of a program code (e.g., a Java method) that is produced by the javac compiler, and stored in the class file. The information stored in the class file includes, for example, the type information, and the control flow.

Babylon’s enhanced reflection API empowers developers to access and manipulate these code models at runtime, enabling metaprogramming directly within Java. This capability allows for dynamic generation and manipulation of Java programs, including the creation of GPU code tailored for various hardware accelerators like Intel or NVIDIA GPUs. In fact, this is the purpose of a subproject from Babylon called HAT (Heterogeneous Accelerator Toolkit), which leverages Babylon to provide a GPU backend for the Java platform.

In this article I am going to explore HAT, how developers can start using it to access GPUs for hardware acceleration. We’ll delve into the key API components that enable this functionality, and explain how code is executed. Then, I will also compare HAT with TornadoVM, a Java parallel programming framework to transparently accelerate Java data-parallel workloads on modern hardware, including GPUs.

For full disclosure: I’m one of the architects and the lead developer of the TornadoVM project. However, this exploration of HAT comes from a place of research and genuine curiosity about this emerging technology. My goal is to provide an objective comparison between the two projects. While I’ve strived for impartiality, I welcome any discussion or feedback if anything seems biased.

With this out of the way, let’s get started!

HAT: Heterogeneous Accelerator Toolkit

This blog post reflects the state of the Babylon project as of February 2025. Given the project’s rapid development, some examples may not compile or run correctly in future versions. However, the core concepts and fundamental understanding presented here should remain valuable for readers.

The Heterogeneous accelerator Toolkit offers different interfaces to build applications tailored for GPU execution. The HAT interfaces are grouped into three categories:

- An

NDRangeKernel API to help developers to express parallel kernels. - A Java interface to map memory between Java and hardware accelerators, called

iFaceMapper) - An API for identifying methods to accelerate on GPUs.

Let’s briefly look at each of these components.

NDRange API

HAT is based on the SIMT (Single Instruction, Multiple Thread) model, and the NDRange API serves as the interface for Java developers to create parallel kernels that target this model. In a SIMT model, a single instruction operates on multiple threads concurrently, where each thread can access different data. This SIMT model is also the foundation of other GPU programming interfaces and languages such as CUDA, OpenCL, and SYCL.

In HAT, Java developers use the NDRange API to define kernels (methods that will be offloaded to a GPU). A kernel encapsulates the work to be done per thread, and the NDRange defines the amount of threads to run. This programming model scales very well, independently of the number of GPU cores of the actual graphics card.

Let’s write a simple example, a vector addition. In Java, the vector addition can be expressed as follows:

public void vectorAddition(float[] a, float[] b, float[] c) {

for (int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

}

For clarity, let’s make a couple of simplifying assumptions: none of our vectors will be null, and they’ll all have the same size. This allows us to focus on the core concepts. Here’s the Babylon/HAT code:

@CodeReflection

public void vectorAddition(F32Array a, F32Array b, F32Array c, KernelContext context) {

int idx = context.x;

float sum = a.array(idx) + b.array(idx);

c.array(idx, sum );

}

This example demonstrates an explicit parallel kernel. Several key changes are worth noting:

- Annotation: A new annotation (

@CodeRefection) is required to instruct thejavaccompiler to generate a code model that represents the whole method. - Type Changes: The parameter types have been modified from

float[]toF32Array.F32Arrayis a type provided by HAT, representing data structures compatible with the GPU. We’ll dive deeper into HAT’s type system and memory management in the next section. - Kernel Context: A new parameter, the kernel context, is introduced. This special object provides access to GPU built-in intrinsics, including thread IDs and other GPU execution parameters like the maximum number of threads.

- Thread-Based Execution: The traditional for loop has been replaced. Instead, the thread ID, obtained from the kernel context, is used to access data. This is a standard GPU programming pattern: the number of threads launched typically corresponds to the size of the input arrays.

Those familiar with CUDA, OpenCL, or oneAPI will find this code structure very familiar. This similarity is a point that I’ll revisit when comparing HAT with TornadoVM.

Memory Mapping

This is one of my favourite parts of the HAT project. HAT defines an interface called iFaceMapper to represent data. Data is actually stored off-heap by leveraging the Panama Memory Segments API for GPU computing.

From my point of view, data representation presents a significant challenge in GPU programming with managed runtime languages like Java, particularly concerning the tradeoffs between performance, portability and ease of use. It is also a critical part, because in Java, we have the Garbage Collector (GC), that can move pointers around if needed.

HAT tackles this issue by defining a base interface capable of handling data access and manipulation within Panama Segments. This interface is extensible, enabling developers to create custom data objects compatibility with GPUs and other hardware accelerators.

This interface offers broad potential benefits, extending beyond Babylon and HAT to projects like TornadoVM. While TornadoVM offers a wide range of hardware accelerator-compatible types, it currently lacks user-side customization for data representation. This interface could provide a very promising approach for integration, enabling greater flexibility and control, and improve TornadoVM further.

For example, to create a custom data object in HAT to store an array that uses a Memory Segment:

public interface MyCustomArray extends Buffer {

int length();

@BoundBy("length")

float data(long idx);

void data(long idx, float f);

// Define the schema

Schema<MyCustomArray> schema = Schema.of(MyCustomArray.class,

array -> array

.arrayLen("length")

.array("data"));

static MyCustomArray create(Accelerator accelerator, int length) {

return schema.allocate(accelerator, length);

}

}

Then, the HAT OpenCL compiler generates a C-struct as follows:

typedef struct MyCustomArray_s {

int length;

float data[1];

} MyCustomArray_t;

Still, a bit of boiler-plate code to add, but it can be used to define custom data types compatible with GPUs. How cool is this?

Accelerator and Compute Context

Let’s look now at the final piece of the API, the Accelerator object the the ComputeContext. These two objects are used to define the backend to use (e.g., OpenCL, CUDA, etc), and the list of kernels we want to offload.

var accelerator = new Accelerator(lookup, Backend.FIRST);

accelerator.compute(cc ->

MyClass.methodToOffload(cc, matrixA, matrixB, matrixC, size)

);

Then:

@CodeReflection

public static void methodToOffload(ComputeContext cc, MyCustomArray matrixA) {

cc.dispatchKernel(size, kc -> myGPUKernel(kc, data));

}

Note that the first parameter of the dispatchKernel method call (size in this case) is the number of threads to be deployed on the GPU.

Example: Expressing Parallel Matrix Multiplication for GPUs

Let’s put all these concepts into practice and implement Matrix Multiplication for HAT. Matrix Multiplication is one of the key routines used for modern workloads, such as Deep Learning, AI and LLMs. Besides, it is a very good application to be accelerated on GPUs.

Let’s start with the Java sequential implementation of the Matrix Multiplication:

private static void runSequential(F32Array matrixA, F32Array matrixB, F32Array matrixC, final int size) {

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < size; j++) {

float sum = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < size; k++) {

float a = matrixA.array((long) i * size + k);

float b = matrixB.array((long) k * size + j);

sum += a * b;

}

matrixC.array((long) i * size + j, sum);

}

}

}

This shows the canonical matrix multiply (three nested loops). In Babylon/HAT we can parallelize the outermost loop as follows:

@CodeReflection

public static void matrixMultiplyKernel(KernelContext kc, F32Array matrixA, F32Array matrixB, F32Array matrixC, int size) {

if (kc.x < kc.maxX) {

for (int j = 0; j < size; j++) {

float acc = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < size; k++) {

acc += (matrixA.array(kc.x * size + k) * matrixB.array(k * size + j));

}

matrixC.array(kc.x * size + j, acc);

}

}

}

This means that the first loop will run in parallel on the target device by deploying as many threads as rows for each of the matrices. Each thread performs the second and innermost loop (a reduction) to sum-up the values per column.

Next, we need to dispatch the kernel.

@CodeReflection

public static void matrixMultiply(ComputeContext cc, F32Array matrixA, F32Array matrixB, F32Array matrixC, int size) {

cc.dispatchKernel(size,

kc -> matrixMultiplyKernel(kc, matrixA, matrixB, matrixC, size)

);

}

Note that this method also contains the @CodeReflection annotation, even though it will not be executed on the device (GPU). This is because HAT can obtain data, and infer types before compiling the code, and obtain the code model for the method to be offloaded. Thus, the annotation helps the HAT compiler and the runtime to manipulate date and generate the correct OpenCL and CUDA PTX code.

You can see the full example here: https://github.com/openjdk/babylon/pull/276. Note that the only method that will be offloaded to a GPU is the matrixMultiplicationKernel. The rest of the code runs on the host side (under the Java platform). But how is the compilation done? Which parts are offloaded and what the final code looks like? Let’s dive in.

How does Babylon/HAT internally work for GPUs?

As of February 2025, HAT supports OpenCL and CUDA backends. There is also ongoing work for a SPIR-V backend (and fun fact, the SPIR-V code generator library is actually the one we -TornadoVM team- developed for TornadoVM, so I was so happy to see such a library being used outside Academia).

HAT works in a two-stage compilation process to reach the GPU source code (e.g., OpenCL C, or SPIR-V), and then another compilation phase performed by the corresponding GPU driver to obtain the final GPU binary.

Let’s discuss the two-stage compilation process first.

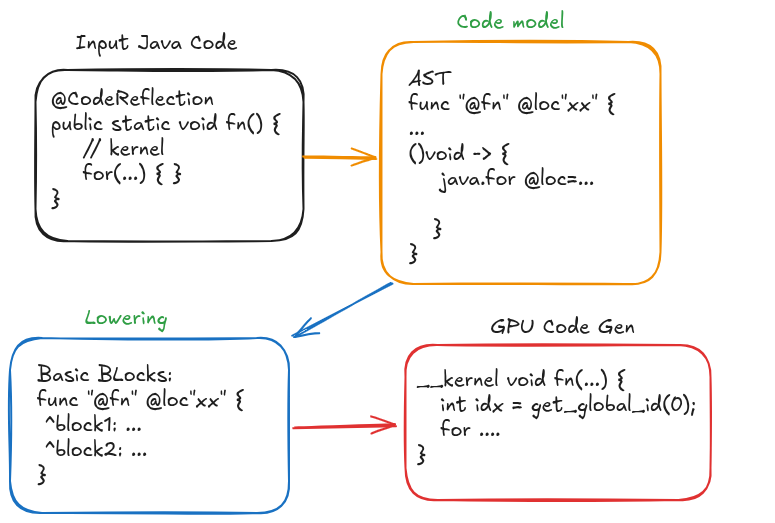

The following diagram shows an abstract representation of the workflow of the different compilation stages to reach the GPU code in Babylon. First, as we saw in the previous example, developers use the NDRange API and the Accelerator Toolkit to annotate and identify the code to be offloaded. Since the method is annotated with the @CodeReflection annotation, the javac compiler generates a code model that is stored in the class file.

This code model is close to an AST (Abstract Syntax Tree) along with types and control flow information. At this point, HAT performs a lowering phase (it actually invokes a lowering phase from the code-reflection API) to transform the original code model into a low level representation. This representation is similar to LLVM IR.

From this code representation, HAT generates the corresponding OpenCL C code (it could also generate CUDA PTX - assembly code for CUDA programs - , or SPIR-V). Once this GPU code is generated, we need another compiler to transform the generated source to GPU binary. This is done by calling the corresponding function from each of the drivers. For example, for OpenCL, the function clBuildProgram will do this.

Note that one could generate GPU code from the code model itself, without lowering. Thus, depending on the target code, this could be an easier choice. However, for SPIR-V or CUDA PTX, I see the lowering phase being a more appropriate level for offloading the code.

For more details: link

Ok, enough talk, let’s see some action!

Installation and Configuration of Babylon for GPUs

Install prerequisites

For Fedora (Checked on Fedora 41)

$ sudo dnf install autoconf alsa-lib-devel cups-devel libXtst-devel libXt-devel libXrender-devel libXrandr-devel libXi-devel

for Ubuntu (Checked on Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS):

sudo apt-get install autoconf libasound2-dev libcups2-dev libfontconfig1-dev libx11-dev libxext-dev libxrender-dev libxrandr-dev libxtst-dev libxt-dev

Installation of Babylon Code-Reflection with OpenJDK 24

Babylon and HAT are in continuous development. Thus, build instructions may change in the future, The following instructions are based on Babylon (commit ee3da03).

# as in February 2025

sdk install java 23-open

sdk use java 23-open

Configure Babylon (Java JDK with Babylon Port)

First, we are going to configure Babylon by building JVM from the source code. Then, we are going to use the resulting JVM to compile and run HAT programs on GPUs.

cd workdir

ROOT_BABYLON=`pwd`

git clone https://github.com/openjdk/babylon.git

bash configure --with-boot-jdk=${JAVA_HOME}

make images

Now we get a new OpenJDK version:

export JAVA_HOME=$ROOT_BABYLON/babylon/build/linux-x86_64-server-release/jdk

export PATH=$JAVA_HOME/bin:$PATH

Configure HAT

cd $ROOT_BABYLON/hat

source env.bash

java @bldr/args bld

Run Examples on GPUs

E.g., Mandelbrot with the OpenCL backed:

java @bldr/hatrun ffi-opencl mandel

Mandelbrot with the CUDA PTX backed:

java @bldr/hatrun ffi-ptx mandel

Cool, isn’t it? Let’s now run a benchmark and compare it with Java and TornadoVM.

Performance Evaluation of Matrix Multiplication on GPUs

In this section, we are going to evaluate the performance of the Matrix Multiplication on GPUs using Babylon, and compare it against TornadoVM. The following table shows the system CPU, GPU and the software used.

| System | Version |

|---|---|

| CPU | 13th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-13900K |

| GPU | RTX 4090 |

| NVIDIA-DRIVER | 550.107.02 |

| OS | Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS |

| Kernel | Linux 6.8.0-47 |

| RAM | 64GB |

| CUDA | 12.1.r12.1 |

| GCC | 11.4.0 |

| TornadoVM | 1.0.10-dev (5da9549d1) |

| JDK for TornadoVM | OpenJDK “21.0.4” 2024-07-16 LTS |

| Babylon | cd3c7ce9c8a |

| JDK for Babylon | openjdk 23.0.1 |

Examples:

Let’s run the Matrix Multiplication explained in the previous section and compare it with TornadoVM. The full example in Babylon can be found in the following link:

https://github.com/jjfumero/babylon/tree/dev/examples/hat/examples/matmul

The TornadoVM version can be found here:https://github.com/jjfumero/tornadovm-examples.

In this post I am not explaining how to program with TornadoVM. If you are interested, I recommend a previous article in which I go into the details about how TornadoVM is used to accelerate different workloads: https://jjfumero.github.io/posts/2024/23/tornadovm-programming-model.

Backends:

Let’s evaluate the OpenCL C and the PTX backends. For the OpenCL C, I use the Intel Integrated Graphics. Although on my system I could have used the RTX 4090 for OpenCL, at the time of writing this post, Babylon does not support multiple devices or device switching. Thus, to make a fair comparison, I also chose the integrated GPU in TornadoVM.

Compared with TormadoVM, an interesting feature is when multiple GPUs are available, the TornadoVM runtime system automatically reorders the devices and selects the best based on compute capability and number of threads to be deployed. Thus, in my system, the default choice for TornadoVM was the 4090, which in my opinion, is what we want by default.

How to reproduce?

Babylon (OpenCL):

java @bldr/hatrun ffi-opencl matmul

Babylon (PTX):

java @bldr/hatrun ffi-ptx matmul

TornadoVM:

The experiment is taken from the tornadovm-examples project.

Note that we can increment the number of runs to make it match with the Babylon experiment, and remove the 2D level of parallelization, to make it equivalent to the HAT/Babylon example:

git diff

diff --git a/src/main/java/io/github/jjfumero/MatrixMultiplication.java b/src/main/java/io/github/jjfumero/MatrixMultiplication.java

index 81bf05c..13c5bb1 100644

--- a/src/main/java/io/github/jjfumero/MatrixMultiplication.java

+++ b/src/main/java/io/github/jjfumero/MatrixMultiplication.java

@@ -253,7 +253,7 @@ public class MatrixMultiplication {

*/

private static void mxmTornadoVM(Matrix2DFloat a, Matrix2DFloat b, Matrix2DFloat c, final int size) {

for (@Parallel int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

- for (@Parallel int j = 0; j < size; j++) {

+ for (int j = 0; j < size; j++) {

float sum = 0.0f;

for (int k = 0; k < size; k++) {

sum += a.get(i, k) * b.get(k, j);

@@ -277,7 +277,7 @@ public class MatrixMultiplication {

private static TornadoExecutionPlan createTornadoVMPlan(Matrix2DFloat a, Matrix2DFloat b, Matrix2DFloat c) {

TaskGraph taskGraph = new TaskGraph("mxm");

- taskGraph.transferToDevice(DataTransferMode.FIRST_EXECUTION, a, b) //

+ taskGraph.transferToDevice(DataTransferMode.EVERY_EXECUTION, a, b) //

.task("mxm", Multiplication::mxmTornadoVM, a, b, c, a.getNumRows()) //

.transferToHost(DataTransferMode.EVERY_EXECUTION, c);

TornadoExecutionPlan executionPlan = new TornadoExecutionPlan(taskGraph.snapshot());

@@ -455,7 +455,7 @@ public class MatrixMultiplication {

matrixA.initRandom();

matrixB.initRandom();

- final int RUNS = 10;

+ final int RUNS = 100;

// 6 implementations to compare

ArrayList<ArrayList<Long>> timers = IntStream.range(0, 6) //

To run:

tornado -cp target/tornadovm-examples-1.0-SNAPSHOT.jar io.github.jjfumero.MatrixMultiplication onlyTornadoVM

If we have multiple devices/backends installed with TornadoVM, we can change the device and the runtime by using the flag -Dmxm.mxm.device=X:Y. X and Y are the required device indices. You can check all devices available with TornadoVM with the following command:

$ tornado --devices

Performance Evaluation

OpenCL C on Intel Integrated Graphics

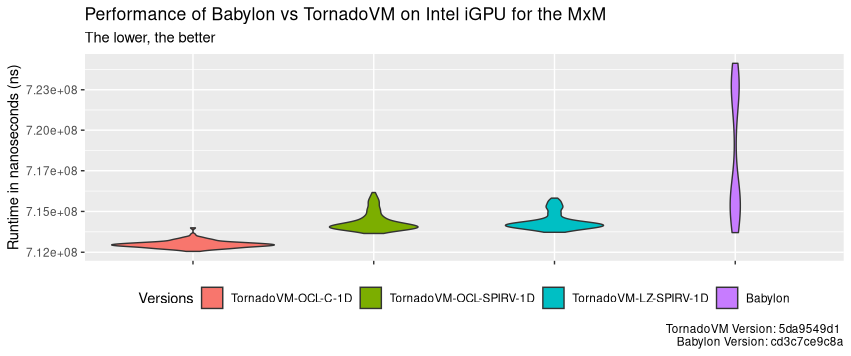

The following performance plot shows the distribution of the run-time across 100 runs for all evaluated versions: namely, a) TornadoVM with the OpenCL backend; b) TornadoVM dispatching SPIR-V code via the OpenCL backend, and c) TornadoVM dispatching SPIR-V code via the Level Zero API. The last bar shows the runtime distribution for Babylon. All these versions run on the Intel integrated graphics. The y-axis shows the total run-time (end-to-end) in nanoseconds. Thus, the lower, the better. The first run of each version includes the JIT compilation time.

As we can see, TornadoVM consistently outperforms Babylon, even with JIT compilation. TornadoVM’s performance is also more stable, with execution times clustered tightly around the average. Babylon’s performance on the same Intel integrated GPU varies more widely, though the total difference between its minimum and maximum execution times is only about 93 milliseconds.

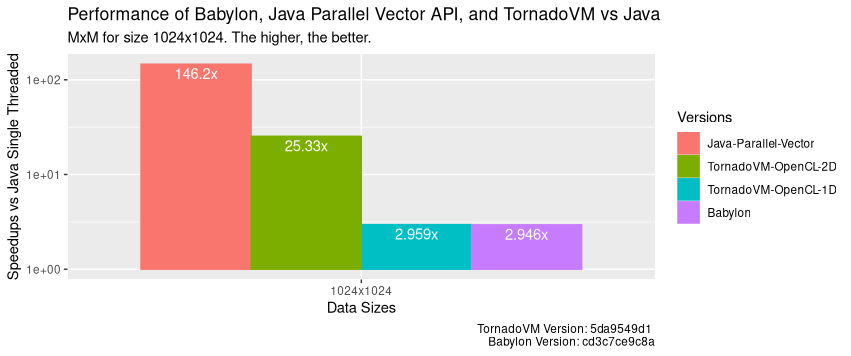

Let’s see the big picture now. Let’s compare each of these approaches with Java and Java Vector API running with Java Streams (the fastest we can get with Java on CPUs). The following performance plot shows speedup against Java sequential run in peak performance (after warm up), and it compares against a) Java Parallel Vector API on CPU; b) TornadoVM with OpenCL C on the intel integrated GPU using a 2D kernel; c) TornadoVM with OpenCL C for 1D kernel; and d) Babylon/HAT.

We see that, for this application, MxM, running on the integrated GPU does not outperform the parallel Java Vector API implementation on CPU.

Take away! Do not underestimate CPU power unless you have a powerful accelerator!

If we include the NVIDIA 4090 GPU, TornadoVM performs up to 2500x compared to Java for the OpenCL backend, as I detailed in a recent technical article!

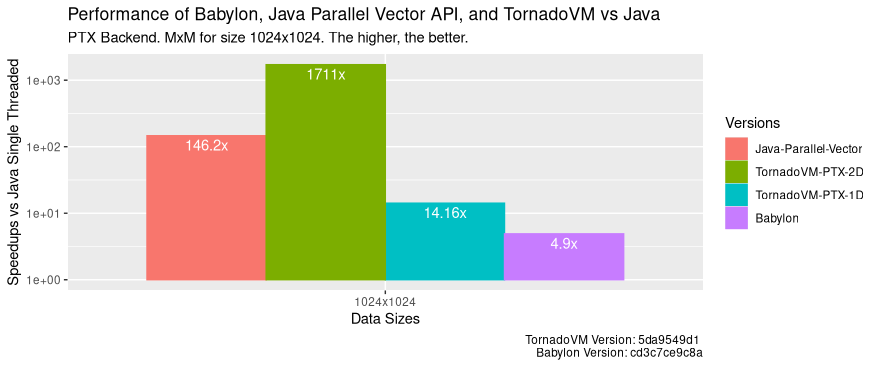

CUDA PTX Backend

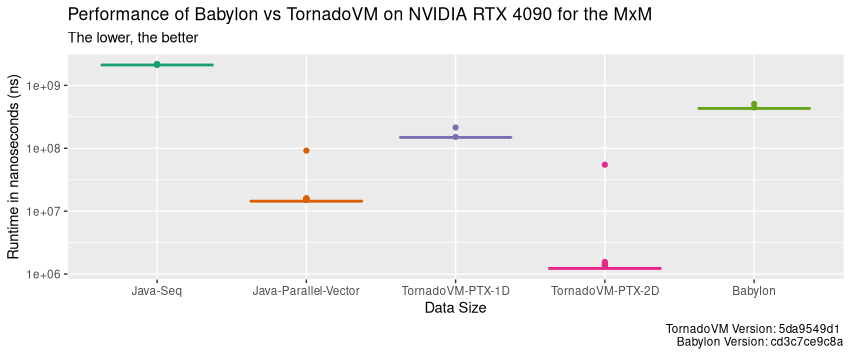

And what about the PTX backend running on the NVIDIA 4090 GPU? The following performance graphs shows the run-time distribution (the lower, the better) of 100 runs for Java sequential version, the parallel Java Vector API version, TornadoVM 1D with the PTX backend, the TornadoVM 2D version and Babylon.

The dots indicate the first execution, in which TornadoVM and Babylon perform the JIT compilation. As we can see, TornadoVM runs faster than Babylon, including the first run in which JIT compilation and execution are involved (2.3x faster for TornadoVM 1D and 9.3x for the 2D version compared to Babylon).

When we compare Babylon and TornadoVM 1D with the parallel Java Vector API, we see that they run slower than the parallel CPU implementation. When running on discrete GPUs, we must consider the cost of offloading, in which we need to consider the data transfers between the main CPU and the GPU, the number of concurrent/parallel operations we will perform on the device. For this particular application, MxM, we are under-utilizing the hardware when we run in 1D.

If you want to see an deeper analysis of the Java Vector API vs TornadoVM, I recommend the following article: https://jjfumero.github.io/posts/2024/12/17/tornadovm-vs-opencl.

By looking at the speeds for the PTX backend compared to Java:

As we see, TornadoVM achieves speedups of up to 1700x compared to Java, 11x faster than CPU execution, and 346x faster than Babylon/HAT for the same GPU.

Does this mean TornadoVM is always faster than Babylon/HAT? No, it does not have to be. For some applications might be faster, other might be slower. As I describe in the next Section more detail, TornadoVM has a JIT compiler and an optimizer, and that can give an advantage for some applications.

HAT vs TornadoVM: Differences and Limitations

Let’s talk about current limitations for both Babylon and TornadoVM. Bear in mind that both projects are in active development, and, what I describe as limitations today (February 2025) might be solved/overcome in near future.

Current Limitations of Babylon/Hat vs TornadoVM

Babylon and HAT are clearly focused on offering an interface to facilitate the manipulation and transformation of Java code. Thus, the main focus is compilation and the minimum runtime support to run the code (e.g., data handling and data representation).

TornadoVM, instead, offers a more complete solution to run on modern hardware accelerators, not just on GPUs. With that, TornadoVM comes a more complex engineering framework to solve adaptive compiler optimizations per architecture, a specialized code optimizer and an optimising runtime systems for different architectures and vendors. Let’s break this down:

Runtime Limitations:

Babylon HAT’s runtime features are currently limited. Compared to TornadoVM, HAT lacks dynamic multiple device selection (e.g., multiple GPUs) and dynamic task-migration. Instead, devices are always statically assigned, reducing adaptability to changing system conditions. Furthermore, it doesn’t support copy operations for data ranges, restricting automatic data management capabilities, for example for automatic batch processing.

Hardware Support and Code Generation:

Babylon HAT currently lacks code generation and a runtime orchestrator for other devices but GPUs. Compared to TornadoVM, which supports GPUs from multiple vendors (Intel, NVIDIA, and AMD), CPUs, FPGAs, and even RISC-V accelerators, Babylon’s hardware support is considerably narrower. While future expansion is likely, the current limitations restrict its applicability. The absence of a code optimizer could impact performance potential on specialized hardware accelerators [4].

Compiler Optimizations:

Babylon does not include an optimizer compiler, at least for now. In contrast, TornadoVM extends the state-of-the-art open source Graal JIT compiler with new compiler optimization pipelines targeted for GPUs, FPGAs and multi-core CPUS, tuning loops ordering, automatic usage of fast intrinsics, automatic use of local/shared memory, etc.

Parallelism and API Complexity:

Babylon HAT lacks native support for 2D and 3D parallelism (or 2D and 3D ranges). While this seems a relatively straightforward feature to implement in the future, its current absence restricts the efficient parallelization of multi-dimensional problems. The HAT API, with its Range programming model, requires developers to possess expertise in GPU programming models like CUDA, OpenCL, or oneAPI. While developers with this background can quickly become productive, those without it may face a steep learning curve.

This contrasts with TornadoVM’s dual API approach: a high-level annotation-based system for newcomers and a low-level Kernel API (similar to Babylon’s Range API) for expert developers. I think this dual approach can gather a broader range of developer expertise.

Current Limitations in TornadoVM vs Babylon/HAT

TornadoVM is not perfect, by any means. It is also in continuous development and improving with every new version.

Support for Custom Data Types:

The main limitation of TornadoVM is the lack of customization for user-data types compatible between Java and hardware accelerators. The iFaceMapper is a promising approach to program and handle efficient data structures compatible between hardware accelerators and the Java runtime.

New APIs and Data Types:

This is also valid for Babylon/HAT, but since I am more involved in the TornadoVM project, I can refer to it here. Offering APIs and new types, although crucial to achieve performance, comes with the cost of developers having to learn new APIs. From my view, if these new interfaces are part of the JDK, then it will be easier to adopt these types of technologies.

Code Generation of Structure Programming Languages:

Code generation in TornadoVM is tricky, and for the OpenCL C backend, especially tricky. Going to low-level details, TornadoVM generates code from the Low-Tier in Graal IR, an unstructured flow IR [5]. The challenge here is to generate a structured OpenCL C kernel from an unstructured flow graph. Thus, it is sometimes difficult to generate correct code. A better target, and an easier target, for TornadoVM is CUDA PTX, and SPIR-V, instead of OpenCL C. However, not all vendors (NVIDIA GPUs for example), allow to run SPIR-V for OpenCL. Since Babylon generates OpenCL C code from a close-to-an-AST form, it will be easier to generate correct OpenCL C code.

Maintenance Support:

The fact that TornadoVM offers more backends and support for more devices also comes with the cost of maintenance. For a small team like TornadoVM, there is always the tradeoff between offering new features and keeping TornadoVM working for all possible devices, architectures and operating systems. This limitation, although not in the design, cannot be overlooked.

I would like this to be an active discussion. Do you know/do you see other limitations? Let me know in the comments.

Conclusions and Final Thoughts

Babylon, through its enhanced reflection API and the HAT subproject, offers a very interesting approach to GPU programming within Java. By enabling direct manipulation of code models at runtime, it facilitates the dynamic generation of GPU code.

This article is a brief introduction to Babylon and GPU programming via the HAT project, as well as an idea about current performance, similarities and differences compared to TornadoVM. All of these from the perspective of a person directly involved in GPU programming for Java for the past 12+ years (time flies!).

I like to see HAT happening as an incubator OpenJDK project in the future for the enhancement of the Java platform, allowing Java developers not only to run on modern GPUs, but also on new upcoming accelerators (e.g., new AI accelerators). Babylon/HAT, in my opinion, is a step towards unification and consolidation of APIs and interfaces that help vendors and implementers (like TornadoVM) to be as close as possible to Java while offering high performance.

On that front, I see HAT borrowing ideas and the research done in projects such as TornadoVM, Aparapi and others. For instance, as Gary Frost (main software architect of the HAT project and creator of Aparapi) acknowledged, the HAT Accelerator and Compute-Context API were inspired by the TornadoVM API. Besides, I see ideas borrowed from the Aparapi project.

As I briefly mention, TorandoVM has served not only as an example, but also as a technology enabler, allowing HAT developers to write a SPIR-V backend using the Java framework we implemented to enable the SPIR-V backend in TornadoVM.

Discussions

If you are interested, let’s keep the discussions active:

https://github.com/jjfumero/jjfumero.github.io/discussions/14

Links

[1] https://mail.openjdk.org/pipermail/discuss/2023-September/006226.html

[2] https://openjdk.org/projects/babylon/articles/code-models

[3] https://openjdk.org/projects/babylon/articles/linq

[4] https://jjfumero.github.io/posts/2024/12/17/tornadovm-vs-opencl