Accelerating Java programs on RISC-V CPUs with Vector Instructions

Published:

This article provides a high-level overview of the RISC-V instruction set architecture, illustrating its modular design through the examination of specific processor implementations. Besides, it discusses the current support for Java on RISC-V. Finally, this article explores the acceleration of Java data-parallel applications on RISC-V CPUs utilizing vector instructions. Specifically, I describe how frameworks like TornadoVM and the oneAPI Construction Kit enable significant performance gains compared to standard Java execution, showcasing the potential of RISC-V for data parallel workloads.

This post is based on a recent paper, Leveraging RISC-V Vectorization: Accelerating Java Programs with TornadoVM and OCK at the RISC-V EU Summit 2025, and it is a collaboration between The University of Manchester and Codeplay Software Ltd. through the AERO European Project.

My goal with this article is to expand, in more detail, about the technique and the technologies involved to achieve hardware acceleration on these niche processors. Hopefully, by the end of this article, you will have a better understanding of the RISC-V ecosystem, the status of Java for RISC-V, and a possible approach to enable RISC-V CPUs as hardware accelerators for Java programs.

High-Level Overview of RISC-V

RISC-V is an open standard and royalty-free Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) based on the Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC) principles. It is designed to provide an open alternative to proprietary ISAs, enabling both academia and industry to innovate and craft custom processor designs without licensing fees.

In my view, a key strength of the RISC-V (apart from the open designs) is its modularity and extensibility. RISC-V is built upon modular designs, enabling CPU architects and developers to tailor processors to their specific needs. For instance, a RISC-V 32/64-bit integer base design can be extended with modules for multiply-divide operations, floating-point arithmetic, and vector processing, each meticulously defined within the RISC-V specification.

Furthermore, it allows CPU hardware implementers to pick and choose the modules they need. For instance, If a design doesn’t necessitate FP64 (double-precision floating-point) computations, the ‘D’ extension can be omitted, streamlining the hardware and reducing complexity.

To support the ongoing evolution and maintenance of the RISC-V specification and its ecosystem, RISC-V International (formerly the RISC-V Foundation) was established. This organization plays a crucial role in ensuring the standardization and growth of this architecture through various activities and working groups.

As follows, we will investigate how Java can be used with RISC-V processors, and how it can utilize parallel functional units (such as the vector units) to process data much faster with the help of TornadoVM and the oneAPI Construction Kit.

What options are available for RISC-V hardware in 2025?

RISC-V hardware presents exciting possibilities, but acquiring units was challenging in the past. When I began exploring RISC-V in 2018, hardware availability was extremely limited. Obtaining even a single board was difficult. At that time, Sifive was one of the key players, showcasing a prototype capable of running Linux on a RISC-V64 SoC.

Since then, many companies have emerged supporting and building on RISC-V. As of 2025, I see many Single Board Computers (SBCs) appearing in the market, such as the Banana PI BPI-F3, and Lichee PI 3A. Those are the boards I am using for this blogspot. These two boards are available on Amazon and Aliexpress, and they cost around 150-200 euros each, depending on the internal capacity of the eMMC flash storage and RAM size.

These two SBCs have the same CPU processor, a Spacemit K1 processor that implements a RISCV64 GCVB - RVA22 Profile. Each letter represents an extension, or a group of extensions over the base RISC-V 64 CPU. Let’s break down these numbers mean:

- G represents a group of several extensions: It contains:

- I: Integer base

- M: Integer multiplication and division

- A: Atomic instructions

- F: Single-precision floating point instructions

- D: Double-precision floating point instructions

In addition, this RISC-V implements CVB:

- C: Compressed instructions

- V: Vector instructions. These are the ones we are interested in for the acceleration part with TornadoVM and OCK. More on this later.

- B: Bit manipulation instructions

As you can see, RISC-V’s modular design allows processors to be highly customized. A processor’s capabilities are determined by the specific extensions it includes. To simplify software development for these varying configurations, RISC-V defines standardized profiles. These profiles group common extensions together, providing a target platform for general-purpose processors and making it easier for developers to create compatible applications.For the Spacemit K1 processor, the profile implemented is RVA22:

https://github.com/riscv/riscv-profiles/blob/main/src/profiles.adoc#rva22-profiles

In this way, it will be easier for software developers to build and support applications running on these architectures.

What kind of Operating System can you run?

The Banana PI F3 and Lichee PI3 SBCs support Bianbu OS, a customized Ubuntu-based distribution for RISC-V developed by Bit-Brick (https://www.bit-brick.com/about-us/). While Bianbu was my primary option, other distributions like Debian, ARMbian, and Fedora can also be used, though I haven’t tested them myself.

Installation instructions for Bianbu on the SBC can be found at:

https://wiki.banana-pi.org/Banana_Pi_BPI-F3#System_Image

For better performance, I recommend installing the OS on the internal eMMC memory using the provided Titan Tools. This significantly improves speed compared to running the OS from an SD card. Here are the read throughput benchmarks for the internal SSD.

The difference in read throughput performance is shown in the following examples:

## SD card

sudo hdparm -t --direct /dev/mmcblk0

/dev/mmcblk0:

Timing O_DIRECT disk reads: 240 MB in 3.01 seconds = 79.69 MB/sec

While the read speeds for the internal eMMC storage (where the OS is installed):

## Internal SSD

$ sudo hdparm -t --direct /dev/mmcblk2

/dev/mmcblk2:

Timing O_DIRECT disk reads: 580 MB in 3.00 seconds = 193.31 MB/sec

For even faster performance, I also recommend installing an SSD and working with your files in this space.

sudo hdparm -t --direct /dev/nvme0n1

/dev/nvme0n1:

Timing O_DIRECT disk reads: 1898 MB in 3.00 seconds = 632.25 MB/sec

The following image shows the Banana PI F3 running Bianbu OS 1.0.5. The Banana PI F3 is located on the left-hand side.

Before discussing the entire software stack to run TornadoVM on these SBCs, let’s briefly discuss the processor and the features of each SBC.

As I mentioned, the CPU present in the BananaPI F3 and the Lichee PI 3 from SiPEED is the same, the Spacemit K1 processor, which contains 8 RISC-V cores able to run vector instructions compliant with the RVV 1.0. This is important, for me at least, since the software dependencies for TornadoVM to run on this hardware generate RISC-V RVV 1.0 instructions. There are other RISC-V boards on the market (e.g., the Milk-V Pioneer, but it implements RISC-V RVV 0.7 instead).

$ lscpu

Architecture: riscv64

Byte Order: Little Endian

CPU(s): 8

On-line CPU(s) list: 0-7

Model name: Spacemit(R) X60

Thread(s) per core: 1

Core(s) per socket: 8

Socket(s): 1

CPU(s) scaling MHz: 100%

CPU max MHz: 1600.0000

CPU min MHz: 614.4000

Caches (sum of all):

L1d: 256 KiB (8 instances)

L1i: 256 KiB (8 instances)

L2: 1 MiB (2 instances)

The Banana PI F3 that I got has 4GB of RAM, which, as we will see, can be very limiting when it comes to the installation of some of the software dependencies. At a later stage of the development for TornadoVM, my lab bought the Lichee PI 3 from SiPEED, which has the same processor but 16GB of RAM and 32GB of eMMC flash storage, which makes compilation of LLVM much easier.

So far, we have discussed general aspects of the RISC-V architectures, some real hardware and the OS. Now it is time to run Java.

Is Java available for RISC-V?

Since TornadoVM accelerates Java programs, we need to run Java applications on RISC-V. But, is Java ready for this new CPU architecture?

The first port for RISC-V is JEP 422 which supports RISC-V RV64GV (and by now, we know what these letters mean). This RISC-V port was originally provided by Huawei, and followed up by Alibaba, Rivos, ISCAS and Syntacore. It was merged for JDK 19, and it contains the port for the template interpreter, the C1 and C2 compilers, and all mainline GCs.

Since TornadoVM currently uses JDK 21, the RISC-V port is already included, which is great news!

The one I am currently using is from BellSoft:

$ java --version

openjdk 21.0.6 2025-01-21 LTS

OpenJDK Runtime Environment (build 21.0.6+10-LTS)

OpenJDK 64-Bit Server VM (build 21.0.6+10-LTS, mixed mode)

So, can we run TornadoVM?

TornadoVM depends on the implementation of low-level parallel programming models such as OpenCL, Level Zero or CUDA PTX. As far as I know, there are no Level Zero or CUDA PTX implementations for the RISC-V architecture. However, we can find some implementations for OpenCL.

The oneAPI Construction Kit (OCK for short), and it is defined as a framework to implement open standards for new hardware accelerators. OCK includes a runtime for CPUs to run OpenCL C programs as well as dispatch SPIR-V kernels. And this is exactly what TornadoVM needs in order to accelerate Java methods on new hardware.

But, not only that, OCK can also auto-vectorize OpenCL and SPIR-V programs to run on RISC-V with RVV 1.0 vector instructions, which can potentially increase performance of our data parallel Java methods. Let’s explore what vectorization means, and how it can be enabled before we start running some experiments on this platform.

Vectorization

Vectorization is a parallel computing technique that performs the same arithmetic operation on multiple data elements at a time. The number of elements processed in parallel depends on the processor’s vector unit capabilities, typically handling 2, 4, 8, 16, or more data items at once. This technique is widely used to accelerate multimedia and data-parallel applications, including LLMs these days!

For example, modern Intel CPUs implement AVX and AVX512 instructructions, which can compute up to 32 FP32 floats at a time.

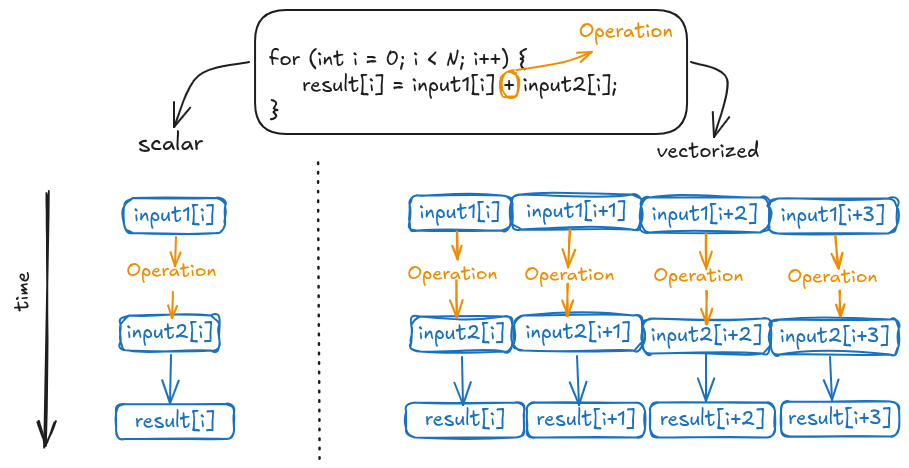

The following Figure shows a high-level representation of vectorization. Consider a for loop performing vector addition. In a scalar execution, each iteration processes a single element from each array, performing the addition, and storing the result in the corresponding position.

Unlike scalar operations, vectorization, as shown in the figure’s right-hand side, enables simultaneous processing of multiple data elements. The figure exemplifies this with a four-element operation. For illustrative purposes, we assume a single CPU clock cycle per operation, acknowledging that actual cycle counts depend on the operation and CPU architecture. However, this simplification effectively highlights the performance benefits of parallel computation. This speedup is achieved through replicated functional units in CPUs equipped with vector instructions.

But how do you write vector code? There are few approaches: a) via libraries, what is called explicit vectorization; b) via constructs in a programming language or a parallel programming model (e.g., the CilkPlus programming model using the array notation); and c) auto-vectorization, in which compilers can generate vector code from a scalar code.

Each approach has its pros and cons. But the auto-vectorization approach is ideal and probably the hardest to achieve. Modern compilers, such as the Java C2 compiler, can auto-vectorize code for x64 and ARM64. However, explicit use of vector units via the Java Vector API can yield to higher performance, as shown in this paper.

But, what about auto-vectorization of OpenCL programs? How does it compare? The rest of the post I am going to explore this.

Workflow for auto-vectorization in TornadoVM with OCK

TornadoVM compiles Java methods from the Java bytecode to OpenCL C, and SPIR-V binary. Then, the resulting optimized OpenCL/SPIR-V code is dispatched via the OpenCL runtime.

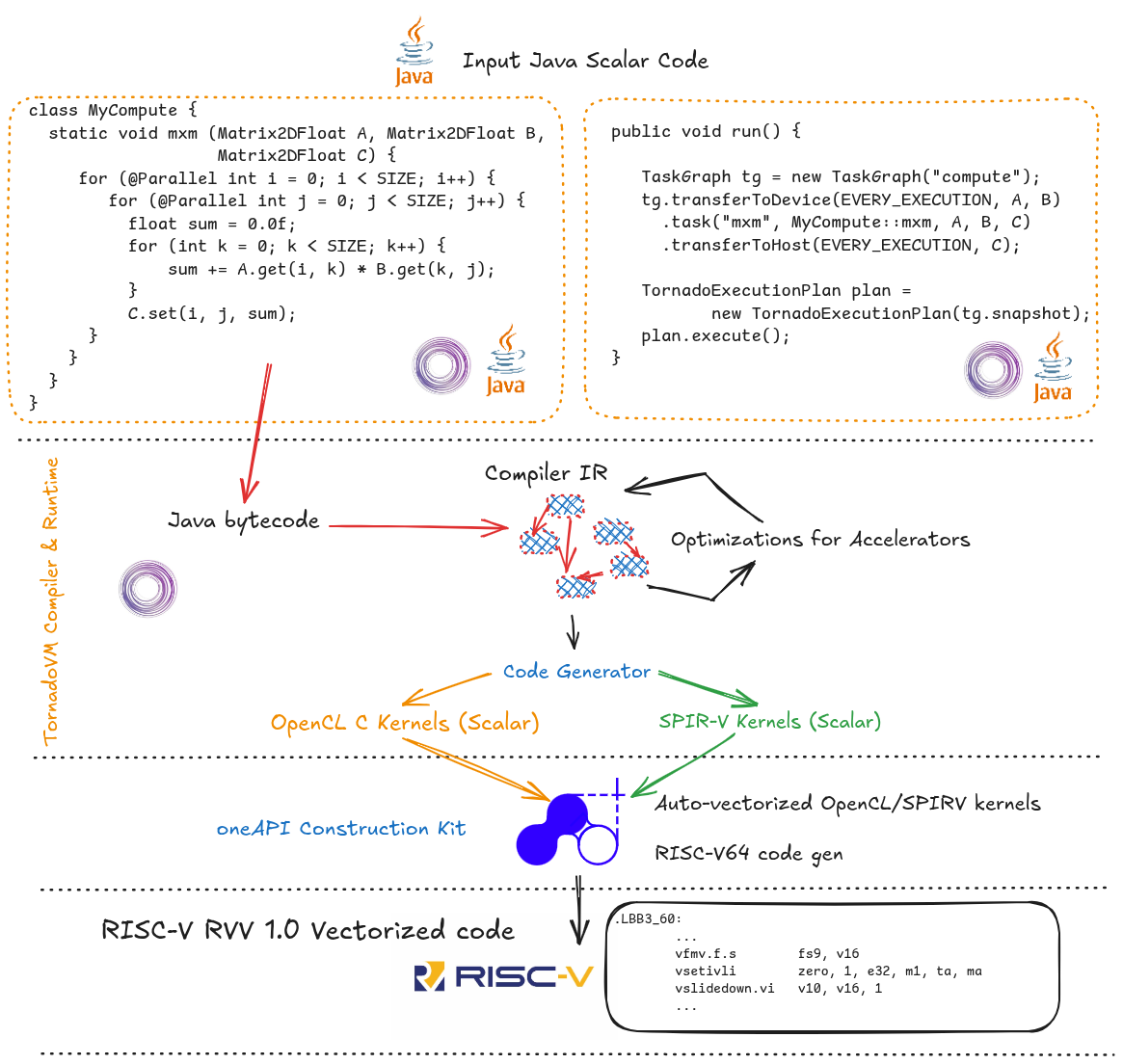

The compilation process is shown in the Figure below. The input application is written using the TornadoVM APIs and it contains three main parts:

- Identify the parallel loops (using the @Parallel) annotation, as we can see in the left-hand side of the Figure. Note that the example represents a parallel version for the matrix multiplication, and it operates on scalar types.

- Task-Graph build: then we build a task graph, which contains the definition of the methods to offload, and the data involved (e.g., arrays and matrices we want to send to the accelerator).

- Finally, we create an execution plan from the task-graph, and execute it.

This overview provides a high-level description of the TornadoVM programming model. For a more detailed exploration, including application development guidelines, please refer to one of my previous posts.

The primary objective of this article is to illustrate the compilation and execution process of TornadoVM on RISC-V, with a specific focus on auto-vectorization.

At runtime, TornadoVM builds a graph (it is actually the Graal IR that represents all methods to offload), and optimizes the code. TornadoVM has a pipeline of many compiler optimizations that are interleaved with current Graal compiler optimizations. Some examples are loop interchange, data parallel loops transformations, intrinsics exploration, etc.

Once the code has been optimized, TornadoVM generates the corresponding OpenCL C/SPIR-V codes. Note that the generated code is still scalar code. No auto-vectorization is applied, just yet.

After the code generation, TornadoVM builds the generated program via the OpenCL runtime using the clBuildProgram. In this step, the generated code is further compiled to the target selected platform. In this case, is the RISC-V 64 CPU platform using OCK.

OCK also contains a JIT compiler to optimize the OpenCL C/SPIR-V code for the RISC-V 64 CPU. In this step, the code is actually auto-vectorized. Thus, from the input Java scalar code, we have reached, hopefully, a vectorized code optimized for RISC-V 64. How cool is this?

Ok, enough talk. Let’s see this in action. The rest of the post I will explain how to compile LLVM, OCK and TornadoVM to run on RISC-V, and show some performance analysis of the traditional Matrix Multiplication application running on this CPU.

Building LLVM and OCK from source

At the time of writing this post (April 2025), there are no prebuilts of OCK for RISC-V 64.Thus, we need to build OCK from source. The OCK source code is an open-source project under the UXL Accelerated Foundation, and it depends on LLVM 19, so we are going to build LLVM from source as well.

Configure the dependencies for LLVM and OCK:

sudo apt install python3-virtualenv python3-psutil

sudo apt install -y build-essential git cmake libtinfo-dev python3

sudo apt-get -y install gcc-riscv64-linux-gnu

sudo apt-get install spirv-tools

Build LLVM:

git clone --depth 1 --branch=release/19.x git@github.com:llvm/llvm-project.git llvm

git clone --depth 1 git@github.com:uxlfoundation/oneapi-construction-kit.git

cmake llvm \

-Bbuild -GNinja \

-DLLVM_ENABLE_DIA_SDK=OFF \

-DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=llvm_install \

-DLLVM_ENABLE_ZLIB=FALSE \

-DLLVM_ENABLE_ZSTD=FALSE \

-DLLVM_ENABLE_Z3_SOLVER=FALSE \

-DLLVM_ENABLE_PROJECTS="clang;lld" \

-DLLVM_TARGETS_TO_BUILD="RISCV" \

-DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Release \

-DLLVM_ENABLE_ASSERTIONS=ON \ -DCMAKE_TOOLCHAIN_FILE=/mnt/data/ock/oneapi-construction-kit/platform/riscv64-linux/riscv64-gcc-toolchain.cmake \

-DLLVM_HOST_TRIPLE=riscv64-unknown-linux-gnu \

-DLLVM_BUILD_LLVM_DYLIB=ON \

-DLLVM_LINK_LLVM_DYLIB=ON

Note that the -DCMAKE_TOOLCHAIN needs to be pointed to the cmake file provided by OCK:

-DCMAKE_TOOLCHAIN_FILE=/path/to/oneapi-construction-kit/platform/riscv64-linux/riscv64-gcc-toolchain.cmake

Then:

ninja -C build install

Keep an eye on RAM, Swapping and Thermals

If you compile LLVM on a board with only 4GB of RAM, you might end up swapping quickly. That was my case when I first built LLVM on the Banana PI F3 4GB. To avoid swapping, you can tell LLVM to build with 1 or 2 threads by adding these two flags in the configure:

-DLLVM_PARALLEL_LINK_JOBS=1 -DLLVM_PARALLEL_COMPILE_JOBS=2

Then:

export CMAKE_BUILD_PARALLEL_LEVEL=1

cmake --build build --target install

Note that compilation may take some time. In fact, in my case, back and forth with some parameter tuning took ~4 days. So, be patient!

Another thing to consider when compiling LLVM is temperature. In my case, the Banana PI F3 did not come with active cooling. With the passive cooling and normal use, it is ok. However, compiling LLVM is another story, and I ended up using an old fan from a laptop just for the time it took to compile LLVM:

Compiling OCK for RISC-V

cmake -GNinja -Bbuild-riscv-hw-vector \

-DCA_ENABLE_DEBUG_SUPPORT=ON \

-DCA_LLVM_INSTALL_DIR=/mnt/data/ock/llvm/llvm_install \

-DCA_ENABLE_HOST_IMAGE_SUPPORT=OFF \

-DCA_ENABLE_API=cl \

-DCA_CL_ENABLE_ICD_LOADER=ON \

-DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=$PWD/build-riscv-hw-vector/install \

-DCA_HOST_TARGET_RISCV64_FEATURES="+v"

ninja -C build-riscv-hw-vector install

Alternatively, to build in a single thread:

export CMAKE_BUILD_PARALLEL_LEVEL=1

cmake --build build-riscv-hw-vector --target install

Final Configuration for OpenCL

$ sudo apt-get install clinfo

$ cd /usr/lib/riscv64-linux-gnu/

$ sudo ln -s libOpenCL.so.1 libOpenCL.so

Additionally, create a new file under /etc/OpenCL/vendors/ with the path to the libCL.so that OCK generates.

cat /etc/OpenCL/vendors/ock.icd

/mnt/data/ock/oneapi-construction-kit/build-riscv-hw-vector/install/lib/libCL.so

Now we can run OpenCL!

$ clinfo

Number of platforms 1

Platform Name ComputeAorta

Platform Vendor Codeplay Software Ltd.

Platform Version OpenCL 3.0 ComputeAorta 4.0.0 Linux riscv64 (Release, 08207aa8)

Platform Profile FULL_PROFILE

Platform Extensions cl_codeplay_kernel_exec_info cl_codeplay_soft_math cl_khr_create_command_queue cl_khr_icd cl_codeplay_extra_build_options

Platform Extensions with Version cl_codeplay_kernel_exec_info 0x1000 (0.1.0)

cl_codeplay_soft_math 0x1000 (0.1.0)

cl_khr_create_command_queue 0x400000 (1.0.0)

cl_khr_icd 0x400000 (1.0.0)

cl_codeplay_extra_build_options 0x6000 (0.6.0)

Platform Numeric Version 0xc00000 (3.0.0)

Platform Extensions function suffix CODEPLAY

Platform Host timer resolution 0ns

Now we are ready to build TornadoVM for RISC-V.

Build TornadoVM for RISC-V

Although TornadoVM is just a Java program, it contains some dependencies that are not fully ported to RISC-V. However, with a small patch, TornadoVM can be installed on RISC-V systems. TornadoVM provides an automatic script to download and patch the code for RISC-V.

First, create a new Python environment:

$ python3 -m venv /mnt/data/python-env

$ source /mnt/data/python-env/bin/activate

$ pip3 install lit

Then, clone TornadoVM and build it with the patch for RISC-V (updated for TornadoVM v1.1.1-dev).

## Clone TornadoVM Repo

$ git clone https://github.com/beehive-lab/TornadoVM.git

## Clone TornadoVM patch repo:

$ git clone https://github.com/beehive-lab/tornadovm-riscv-patch.git

## Build for OpenCL only

$ bash tornadovm-riscv-patch/apply-riscv-patch-opencl.sh

## Build for OpenCL and SPIR-V

$ bash tornadovm-riscv-patch/apply-riscv-patch-spirv.sh

$ source setvars.sh

tornado --devices

Number of Tornado drivers: 1

Driver: OpenCL1

Total number of OpenCL devices : 1

Tornado device=0:0 (DEFAULT)

OPENCL -- [ComputeAorta] -- ComputeAorta riscv64

Global Memory Size: 3.9 GB

Local Memory Size: 32.0 KB

Workgroup Dimensions: 3

Total Number of Block Threads: [1024]

Max WorkGroup Configuration: [1024, 1024, 1024]

Device OpenCL C version: OpenCL C 1.2 Clang 19.1.7

Congratulations! TornadoVM running on RISC-V with OCK. Now, we can run a few experiments and check some performance.

Checking Vector Instructions for RISC-V

We can generate the assembly that the OCK generates from the OpenCL C kernel that TornadoVM generates by enabling the following env variable:

export CA_HOST_DUMP_ASM=1

Then, we can run any example with TornadoVM, and we will see the generated RISC-V assembly code. For example:

tornado -m tornado.examples/uk.ac.manchester.tornado.examples.compute.MatrixMultiplication2D 256

The RISC-V generated code can be very large. But we can see that in some parts of the code vector instructions are used:

.LBB3_33:

add t5, a4, a5

add t5, t5, s4

vsetvli zero, zero, e64, m8, ta, ma

vadd.vx v24, v8, t5

vsetvli zero, zero, e32, m4, ta, ma

vnsrl.wi v20, v24, 0

vmslt.vx v0, v20, s8

vsetvli zero, zero, e16, m2, ta, ma

vmv.x.s a1, v0

slli a1, a1, 48

beqz a1, .LBB3_32

vsetvli zero, zero, e64, m8, ta, ma

li a1, 32

vsll.vx v24, v24, a1

vsra.vx v24, v24, a1

j .LBB3_36

.LBB3_35:

vsetvli zero, zero, e64, m8, ta, ma

vadd.vx v24, v24, s2

vmslt.vx v20, v24, s8

vmand.mm v0, v20, v0

vsetvli zero, zero, e16, m2, ta, ma

vmv.x.s a1, v0

slli a1, a1, 48

add t5, t5, s2

beqz a1, .LBB3_32

Let’s see how this can impact performance.

Preliminary Results on RISC-V

Let’s run an experiment and see the performance we get by enabling auto-vectorization with TornadoVM and OCK. We are going to run the Matrix Multiplication, a common algorithm widely used these days for AI and LLMs.

I run this Benchmark on the RISC-V Banana PI F3 with 4GB of RAM. The OS is Bianbu 1.0.5, TornadoVM 1.0.10 and OCK commit 65036b8. LLVM 19.1.5 and GCC 13.2. The OpenJDK used is 21.0.5.

You can obtain the benchmark from the GitHub repository:

$ git clone https://github.com/beehive-lab/tornadovm-benchmarks

$ cd tornado-benchmarks

$ ./build.sh

To run, you need to copy the setvars.sh from the TornadoVM installation:

cp /path/to/tornadovm/setvars.sh .

source setvars.sh

./run.sh mxm

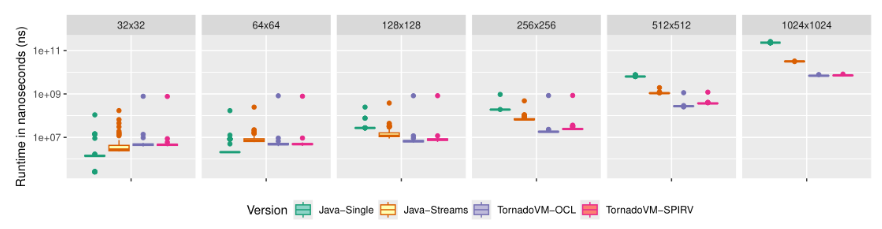

The following plot shows the run-time distribution for the 100 runs. Note that TornadoVM compiles the Java code in the first iteration, and then it runs directly with the compiled code.

The performance plot is read as follows. The x axis shows different data sizes for the matrix multiplication. Each size was evaluated with Java single threaded, Java with parallel streams, and then TornadoVM using the OpenCL backend and TornadoVM using the SPIR-V backend. The y-axis shows runtime in nanoseconds. Thus, the lower, the better.

For small matrices, the Java sequential version performs very well. The cost of multi-threading and runtime thread-scheduling are not worth it for small data sizes. There is no auto-vectorization for the Java code, as in April 2025. The Java streams version performs up to 8x in this 8-core machine.

However, for TornadoVM, performance is even higher, up to 32x faster than Java Sequential, and up to 4x faster than Java Streams for the same CPU. This is the effect of the auto-vectorizer and the multi-threaded execution. Another highlight is that, for large matrix sizes (e.g., 512 and 1024) even the first iteration (which includes optimization and compilation) runs faster than the parallel stream execution.

Conclusions

This post has shown a general introduction to RISC-V, the modularity of RISC-V processors and a high-level overview of how ready is Java to run on RISC-V. Additionally, this post has shown how to increase performance of data parallel applications written in Java using TornadoVM and the oneAPI Construction Kit to exploit auto-vectorization in RISC-V processors.

The preliminary results from the Matrix Multiplication benchmark show a substantial speedup with TornadoVM compared to sequential Java and Java streams, highlighting the effectiveness of auto-vectorization and multi-threaded execution on RISC-V. While challenges exist, such as the need to build software from source and manage limited resources, the advancements in hardware availability and software support make RISC-V a very appealing platform for many developers, including Java developers.

Discussions

If you are interested, let’s keep the discussions active:

https://github.com/jjfumero/jjfumero.github.io/discussions/15

Appendix

When using LLVM 19.1.7, I noticed an error in a duplicated definition. The error is as follows:

/mnt/data/ock/oneapi-construction-kit/modules/compiler/builtins/source/builtins.cl:10675:27: error: conflicting types for 'printf'

10675 | int __attribute__((weak)) printf(const constant char *const restrict fmt, ...);

| ^

/mnt/data/ock/oneapi-construction-kit/modules/compiler/builtins/include/builtins/builtins.h:16367:27: note: previous declaration is here

16367 | int __attribute__((weak)) printf(const constant char* const restrict fmt, ...);

| ^

1 error generated.

[6/4830] Building CXX object modules/compiler/compiler_pipeline/CMakeFiles/compiler-pipeline.dir/source/define_mux_dma_pass.cpp.o^C

By removing one of these definitions, you can build OCK:

diff --git a/modules/compiler/builtins/source/builtins.cl b/modules/compiler/builtins/source/builtins.cl

index 1c96f2d1..2ef30343 100644

--- a/modules/compiler/builtins/source/builtins.cl

+++ b/modules/compiler/builtins/source/builtins.cl

@@ -10672,7 +10672,7 @@ void __CL_BUILTIN_ATTRIBUTES prefetch(const global double16 *pointer,

/*-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-*/

-int __attribute__((weak)) printf(const constant char *const restrict fmt, ...);

+//int __attribute__((weak)) printf(const constant char *const restrict fmt, ...);

/*-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-*/

Compile again:

ninja -C build install