Enabling Transparent Acceleration of Big Data Frameworks Using Heterogeneous Hardware

Published:

Key Takeaways:

- Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) and Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) are powerful hardware that can be used to increase the performance of Big Data applications, and they are really appealing for integrating into the execution workflow of Big Data frameworks, such as Apache Spark and Apache Flink.

- Exploiting heterogeneous hardware for Big Data Workloads is usually done by introducing new APIs, resulting in more complex programs to develop, understand, and maintain. But, what if we do not change/extend the original programming model? Is it possible? This post discusses a new approach to do so.

- This blog post analyses the main reasons why this is a complex problem, and it introduces a co-design approach for enabling seamless GPU and FPGA execution for existing Java Big Data frameworks.

- The co-design approach involves the architecture of software components that can understand each other at different levels of the software stack (e.g., the execution plan orchestrator for distribute execution, the runtime system that handles execution on heterogeneous hardware, and the Just In Time Compiler for GPUs and FPGAs).

Introduction

We recently got a paper accepted for the upcoming VLDB 2023, led by Maria Xekalaki during her PhD, about a study of how current Java big data frameworks can enable seamlessly heterogeneous execution to run on GPUs and FPGAs (or any other type of accelerator). This paper presents the main challenges that limit transparent acceleration, and proposes a co-design technique across various levels of the software stack to run efficient big data workloads from Java without any code modifications.

In this post, I will summarize the main key findings of this paper, and briefly explain the techniques that were implemented. For all the details, you can follow the public pre-print of the paper.

As a proof of concept, we accelerated Apache Flink applications written in Java for the map and reduce parallel operators. To enable seamless GPU/FPGA execution, we integrated Flink with TornadoVM (a parallel programming framework for accelerating Java programs on heterogeneous hardware) into Flink. But, as we will explain in this post, this is not as easy as plugging in the two systems. What we want to achieve is code portability and hardware flexibility. But, as we will explain in this post, this has a cost.

But wait, isn’t this problem already solved?

Well, from our perspective, not really. There are already solutions such as NVIDIA RAPIDS API developed by NVIDIA for accelerating Big Data workloads for Apache Spark on NVIDIA GPUs, and Flink using JCUDA and JCublas. However, these solutions require code modifications from the original big data program in order to use the GPU.

Additionally, these solutions usually make use of pre-built GPU kernels (GPU pre-compiled programs) for specific operators and functions. Thus, if developers want to update the GPU or use different hardware accelerators, or execute on GPUs for a different set of operators, this solution can increase code complexity, maintenance of the entire system, and create additional dependencies for specific hardware and software.

Note that we do not argue that code modifications are bad. When developers want to accelerate their code on GPUs, they are usually willing to learn new tools, new frameworks, and new APIs. This is because performance is a must, not just a “nice to have”. And this is not necessarily a bad thing. However, the way that GPU/FPGA are integrated into existing big data frameworks, creates dependencies in the code base that are quite difficult to maintain and evolve for future accelerators and new programming models (unless all of them use the same low-level interfaces, but in my opinion it is quite unlikely).

But, what if?

What if we would not introduce any new API, just because we want to use a GPU, or an FPGA? Is it possible? To guide the answer, I need to explain some context.

The Big Data framework we are using is Apache Flink. Flink provides a set of parallel skeletons (or algorithms skeletons) that are very well known in the parallel computing literature, such as map, reduce, filters, etc. Some of these parallel skeletons are also particularly good targets to be accelerated on GPUs and FPGAs (such as map and reduce).

Thus, in theory, there should be a way to reuse these skeletons and be able to offload code to these accelerators. If this is the case, why should we introduce new APIs then? Short answer: efficiency. As I mentioned before, if we, developers, are using GPUs, is because we prioritise performance for some of the tasks in our code base. So, to perform tasks fast, especially from programs written in high-level programming languages such as Java, we would want to avoid type conversion and marshalling and dispatch the GPU/FPGA code as fast as possible. So, it seems reasonable to provide frameworks with new types and functions that GPUs can directly understand without any pre/post processing.

But, if this is the case, how bad (in terms of performance) it is not to provide a new API? Is there a way in which we can bypass these challenges? This is what our paper is all about. As follows, I will briefly explain how we approached the problem and the solution/system we propose.

Enabling seamlessly heterogeneous execution on GPUs and FPGAs for Apache Flink

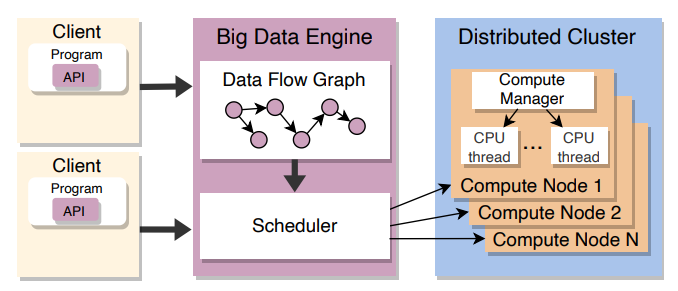

Before showing the details for enabling transparent execution of big data frameworks using hardware accelerators, let’s explain how Flink works. Figure 1 (taken from the paper [1]), shows the typical architecture of big data frameworks. It has three main distinguishable components: a) a client; b) a data engine (which Flink names Job Manager); and set of compute-nodes (which Flink names Task-Managers).

Figure 1: Overview of Big Data Frameworks

The client represents the user application, expressed using the user APIs for data streaming and big data processing (e.g., DataSet API in Apache Flink). The client expresses the computation as a chain of operators (e.g., map, reduce, filters, etc). Then, the big data engine creates a graph of execution, and schedules the job to be done in a distributed cluster (compute nodes physically distributed in a network). Each of the nodes in the distributed cluster runs a set of compute-managers (named Task-Managers in Apache Flink). This is the software component that runs the user code with the corresponding data assigned by the Job-Managers.

This software architecture is well suited for running fast streaming application on CPUs. However, when running on heterogeneous hardware, there are also other things to consider, such as the level of parallelization, the data format representation, and how many threads are deployed on the target accelerator.

To give an example, GPUs are a really desirable choice for exploiting embarrassingly parallel applications, in which independent work can be assigned to different physical cores with minimal or no communication between them. However, even if our application is fully parallelizable, to get the advantage of the computation power of the GPUs, we also need to run a large amount of data. But frameworks such as Apache Flink are designed for streaming and processing single data elements fast. Thus, this design, a-priori, does not facilitate taking advantage of hardware accelerators (unless they use shared memory). But even if we execute on shared memory GPUs, we must consider other things such as data layout.

So what do we need to automatically execute on GPUs/FPGAs?

We need: a) a way to be able to express the computation in such as way we can take advantage of processing large amounts of data in a single request to an accelerator. Thus, we minimize communication between the main CPU and the device (e.g., a GPU); b) we need a way to have the data ready, in a specific format that is GPU/FPGA friendly, to transfer fast and start computing as soon as possible; and c) we need a component that can dynamically compile Java-Flink code to GPU/FPGA-friendly code (e.g., OpenCL, CUDA, oneAPI, etc).

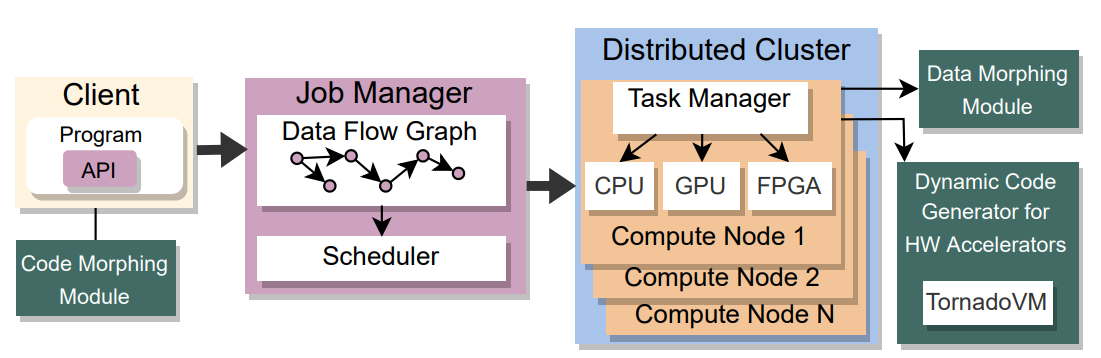

To do so, we extended Apache Flink and TornadoVM with the following software components, highlighted as green in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Architecture of the proposed system

Namely, these components are:

A. Code Morphing: a component for code transformation of User Define Functions (UDFs) that process elements in a fine-grain manner to course-grained.

B. Data Morphing: a component for transforming the data from the internal byte-buffers of Apache Flink into GPU arrays.

C. Just In Time Compiler. Runtime Code Generation from Java-Flink to OpenCL: a component that invokes a JIT compiler for generating OpenCL C code from the results of the code-morphing component.

Note that all code transformations happen at runtime, without user intervention. As follows, I will briefly explain each of these components.

A) Code Morphing

To understand why we need code morphing, let’s look at a code-snippet of a map operator in Apache Flink:

public class MyComputeVector implements MapFunction<Tuple2<Double, Integer>, Double > {

@Override

public double map(Tuple2<Double, Integer> t) {

return t.f0 * t.f1;

}

}

The example shows a straightforward way to multiply two vectors in Apache Flink. The way this is done is by creating a DataSet that contains an array of Tuple2 objects. Each tuple represents the data container for two values. Therefore, Flink user expresses the work to be done per data-item. This is great for scalability since the code should run for 1 core or 1000 cores. But, where do we “inject” the code for the GPU/FPGA?

At least two options:

- Inside the map operator. But this means that each CPU thread, will launch a GPU kernel, which also would mean that, to increase performance, each of the CPU threads that runs the map expression in Flink would have to receive not just a single data-item, but a bulk of them. This is the way Flink proposes:

https://flink.apache.org/news/2020/08/06/external-resource.html

However, this forces developers to diverge code-base and have a specific version for GPU compute. Is there any other way?

- If we look at how a map function operates, it is actually pretty simple. The logic of a map operator is represented in the following pseudocode. If we name the function that would be implemented in Flink

f, thenfrepresents the work to be done per thread. Therefore, to computefover the whole dataset:

for every input from DataSet:

apply(f)

Since this function represents a map parallel skeleton, each element can be compute fully in parallel. Therefore the new function can be represented as:

parallelFor every input from DataSet:

apply(f)

Thus, the idea is to wrap-up the function f, and create a new function that invokes the user function for the whole data set. By doing this, we are changing the granularity in which this function will be executed.

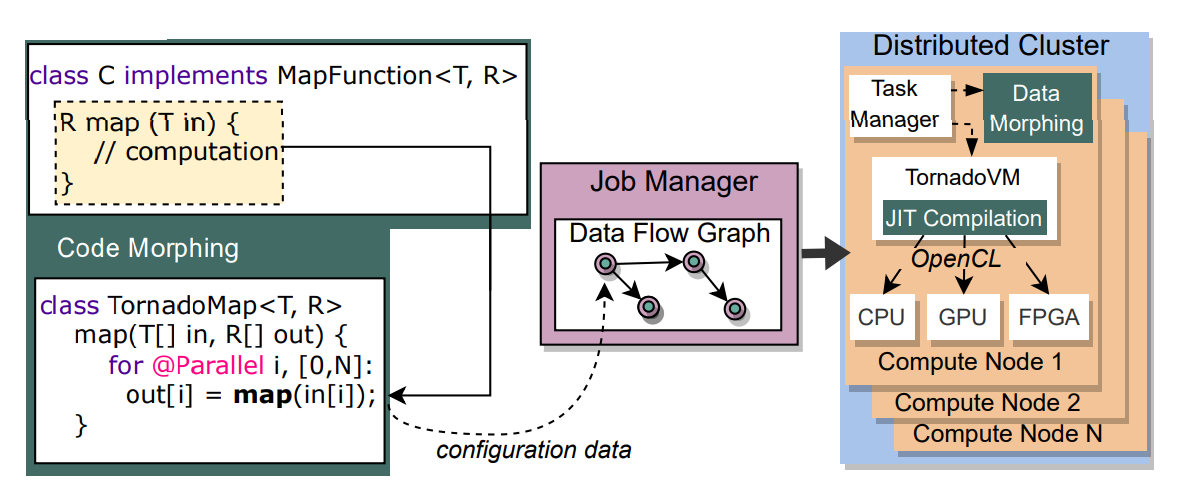

But, what do we get? It turns out, frameworks such as TornadoVM knows how to parallelize the entire function when the code is written in this form. Figure 3 shows a representation of this code transformation.

Figure 3: Workflow of runtime transformation for code morphing

For the details about this transformation, I will refer to the paper. But in a nutshell, the code morphing component makes use of the ASM Java library to transform code at runtime and dynamically create new functions. Cool, isn’t it?

So what have we got until this point? Simplicity for the developer. Since all these transformations happen dynamically and automatically at runtime, developers do not have to worry about changing or adapting the UDFs in order to execute on GPUs or any other accelerator.

Just a last point before moving on. The code-morphing transformations happen on the client side, in the runtime logic before sending the UDFs to the Job-Managers.

B) Data Morphing

Code-morphing is not enough. As we mentioned earlier, we also need the data in the right format. In my opinion, this is an especially important topic, and it is usually underestimated when running on heterogeneous computing systems from high-level programming languages, such as Java.

The reason to do data-morphing is related to the data format in which Flink sends and receives data. Apache Flink is a distributed computing system. Thus, data needs to be serialized and sent from the client, or data-stores to the Task-Managers. But TornadoVM uses its own objects for representing I/O data separately. To avoid extra object creation to make Flink and TornadoVM compatible, the TornadoVM memory manager has been extended to accept Flink serialized buffers, which represents both input and output.

One more thing about buffer serialization: we saw that Apache Flink uses big-endian layout representation, while GPUs and FPGAs, via the OpenCL programming model, use little endian. Therefore, we had to reverse the bytes of each input/output array before running on the accelerator.

Additionally, since a single byte-buffer is used to express all input and output arrays, some GPU vendors require data padding, such as on NVIDIA GPUs. Therefore, our code morphing also adds padding when needed.

From our perspective, this design is not ideal, and if we want to include GPU/FPGA upstream, we should design a better data layout in order to avoid all these conversions. As we will see in the evaluation section, there is room for improvement. And most of it is related exactly to this part.

In general, to allow managed runtime environments automatically exploit GPUs and FPGAs, no matter how good the JIT compiler is that, if the data management is not optimised, we are not going to get performance.

As a side note, I did my PhD on GPU for managed runtime programming languages and part of it was the study of the impact of marshalling and unmarshalling for GPU applications from Java. I showed that, if data representation is not carefully design, marshalling and unmarshalling on for GPU compute can take up to 90% of the total time of the program execution. That’s not ideal. What we really want is to have the “bottleneck” in the computational part.

C) Just In Time Compilation

In addition to code morphing and data morphing, we also extended the OpenCL JIT compiler of TornadoVM with the goal of allowing to access and retrieve data from/to the Flink byte buffers. Since Flink it is a Java framework for big data, the buffers can contain lists of diverse tuple size (any range between 2 and 25), that in turn, can contain collections, arrays, etc.

The TornadoVM’s JIT compiler has been extended to understand Flink’s data structures and directly compile and access the right memory positions for each data structure on the GPU/FPGA’s global memory. These compilation optimizations include new compilation phases for:

- Performing object replacements: the TornadoVM JIT compiler will substitute field loads/stores with access to memory in an array form. Note that TornadoVM will get an array of byte array for representing the whole collection (the part of the collection to be computed for each specific Task-Manager). Therefore, the TornadoVM compiler will update field loads/stores accesses to array accesses for the input byte array.

- Performing correct offset and padding calculations from/to the accelerator’s global memory. These are the cases in which data types differ and some compute platforms need to perform padding (e.g., on NVIDIA GPUs).

There are also other three compilation phases, that are explained in detail in the paper, but basically, they are a combination of these two to cover corner cases (e.g., tuples that contains arrays as fields, matrices, and/or collections).

Performance Evaluation

The paper contains a very detailed performance evaluation. Thus, in this post, I will explain briefly the most significant case scenarios.

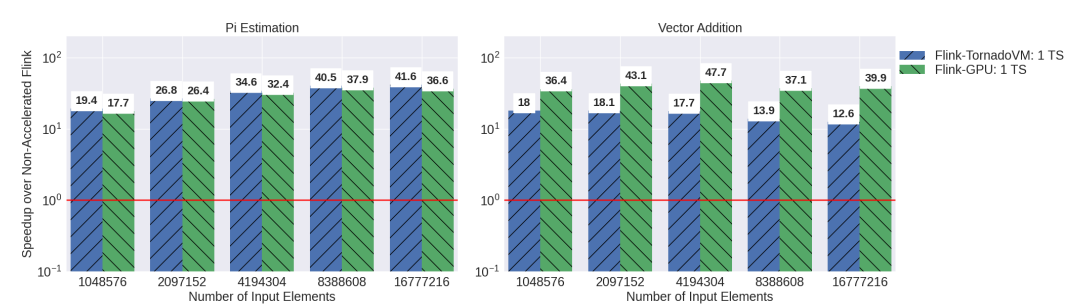

a) Compared to the existing GPU frameworks for Flink

Figure 5 shows the performance of two benchmarks (PI-computation on the left hand side and vector addition on the right-hand side) compared to a single threaded Flink task. We opted for this setup to compare, as fair as possible, Flink-TornadoVM with Flink GPU using JCUDA [6]. Our approach generally outperforms Flink-JCUDA. In a closer analysis, we saw that this is due to the marshalling and unmarshalling of the data from the Tuple form to plain primitive arrays in the case of Flink-GPU, while in our case, we tried to reuse the byte-buffers that Flink provides (although it needs manipulation, as we explained in the data morphing section).

Figure 4: Performance of Flink-GPU vs Flink-TornadoVM

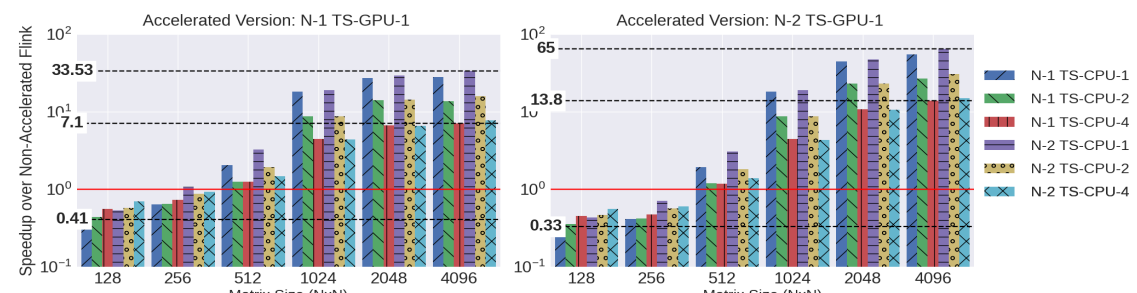

b) Performance on GPUs with multiple nodes

Figure 5 shows a performance evaluation with different Flink configurations - ranging from 1 node (N1 ) to 2 nodes (N2), and 1 to 4 physical threads (CPU-1-4) - in comparison with a single node with a NVIDIA GPU (the higher, the better). The application launched is the classical matrix multiplication. The application is expressed in Flink and it is the same code for every configuration. We see that, when running with a matrix size larger than 512x512, our approach achieves better performance, including the cost of marshalling, padding and byte buffer preparation for TornadoVM.

Figure 5: Performance evaluation of Flink-TornadoVM on GPUS

As a side note, even for the “small” matrix size of 128x128, running these types of applications on GPUs, we should be able to obtain speedups. So there are some fundamental issues to be discussed in the design. But we will analyse those issues in the case d).

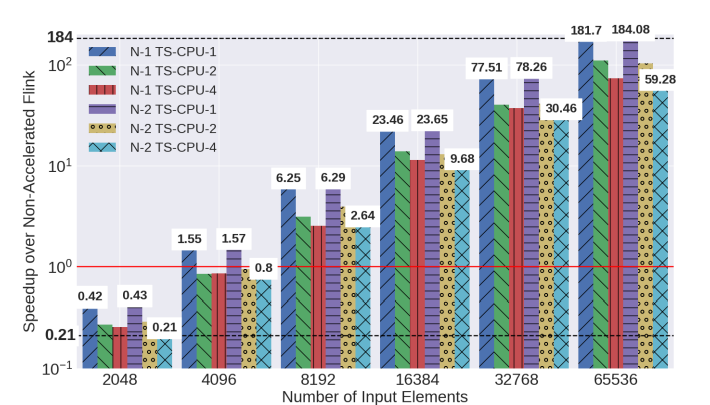

c) What about performance on FPGAs?

As shown by Papadimitriou et al. [7], it is hard to obtain performance for FPGAs from languages such as OpenCL. However, FPGAs are very good for exploiting applications that can use the internal hardware units for specific purposes, such as digital signal processing. As we discussed in the paper, we also noticed that most of the applications we executed, do not benefit from FPGA hardware acceleration. However, for DSP data processing, we were able to obtain high speedups compared with Flink and multiple nodes.

Figure 6 shows the speedup over the Flink non-accelerated implementation using different configurations (1 and 2 physical nodes with 1 to 4 physical threads). As we can see, when running with a large input data set, TornadoVM-Flink is able to achieve up to 180x.

As a side note, the FPGA execution of TornadoVM used a pre-built compiled binary using the code that TornadoVM compiler emits. This is because the compilation from OpenCL to the bitstream (FPGA binary), can take up to three hours. However, all experiments include the data preparation time, code morphing and padding buffer preparation.

Figure 6: Performance evaluation of Flink-TornadoVM on FPGAs

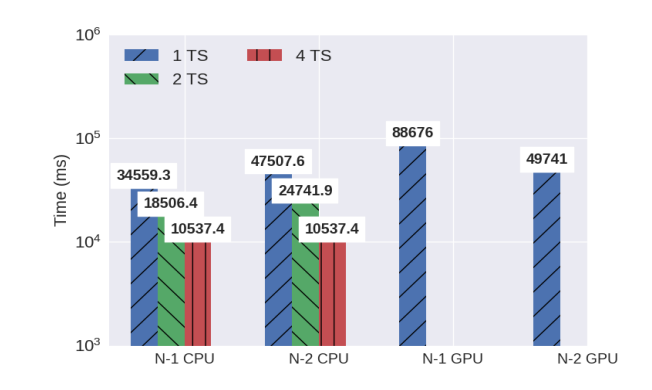

d) But, is Flink-TornadoVM prime for acceleration?

To answer this question, we also study more complex cases. We execute a linear regression application expressed in Flink with very large input data sets (1GB, which was the largest data size TornadoVM could run in a single memory buffer).

Figure 7 shows the result (Figure 11 from the paper [1]). The vertical axis shows the total execution time of Flink (first two groups of bars) and Flink-TornadoVM (last two bars). As we see, the accelerated version with TornadoVM is more than 2x slower than Flink. Why is this?

Figure 7: Performance evaluation of Flink-TornadoVM on GPUs for Linear Regression

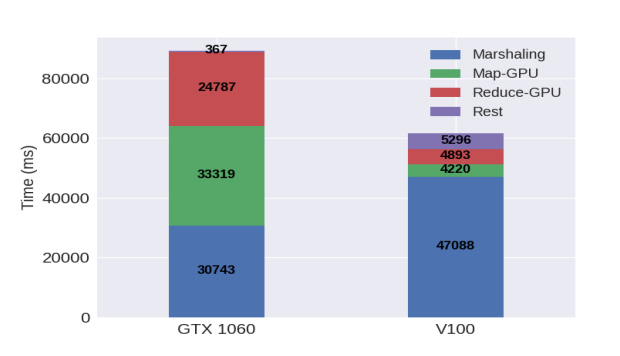

To answer that question, we profiled the execution workflow that enables GPU execution within Flink using our approach. See Figure 8. We saw that most of the time is spent is marshalling the data. This is preparing the data for TornadoVM by reversing the bits (from big endian to little endian, applying the padding for each field within the Flink byte buffer, and applying memory alignment). The Marshalling is represented in colour blue in the next Figure. The computation is represented as green and red for the map and reduce operators, respectively.

The breakdown analysis on the left-hand side corresponds to the execution on the NVIDIA 1060. We also executed the same application on another GPU, V100 to check if our approach is really limited by the kernel time. We saw that, as expected, the execution time for the map/reduce operators decrease, while keeping the marshalling time. This is a memory bound problem.

Figure 8: Breakdown analysis of GPU workflow in Flink-TornadoVM

So, what do we conclude?

- It is possible to automatically run existing Java big data applications on heterogeneous hardware. But it needs a system that is co-designed with the lower-level programming models to run efficiently. Co-design involves techniques for code and data morphing, as well as having a JIT compiler for accessing GPU/FPGA memory efficiently.

- Data representation and memory layout is the key to achieving performance. Things like having the right endianness, padding and alignment can decrease execution time drastically.

We hope this work can be used as a starting point for designing future big data platforms that want to use accelerators as transparently as possible. As mentioned, this blog has shown a summary of the key findings of our VLDB’23 work. For all the details, experiments, and benchmarks, you can follow the paper [1].

Follow-up and discussions

For further discussions, feel free to contact us, and/or add your comments and feedback on GitHub.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Athanasios Stratikopulos and Maria Xekalaki from The University of Manchester for the constructive feedback.

References

[1] Paper: https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/233043755/MXekalaki_vldb2023.pdf

[2] Apache Flink: https://flink.apache.org/

[3] Apache SPARK: https://spark.apache.org/

[4] NVIDIA RAPIDS: https://nvidia.github.io/spark-rapids/

[5] TornadoVM: https://github.com/beehive-lab/TornadoVM

[6] JCUDA: http://javagl.de/jcuda.org/

[7] https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.16304