Introduction to Level Zero API for Heterogeneous Programming

Published:

Key Takeaways & Outline

- Level-Zero is a close to bare-metal API for programming heterogeneous architectures.

- Level-Zero is shipped as part of Intel oneAPI, but it can be used as a standalone API.

- This article shows the basic architecture, what is used for and an example for dispatching matrix multiplication on the Intel HD Graphics with SPIR-V.

- After a few months using the Level-Zero API, in this article, I also show and explain the areas I consider missing or to be improved.

1 - Introduction

Back in March 2020, Intel released a new low-level programming API for heterogeneous computing architectures called Level-Zero. As the name implies, it is a low-level API for accessing heterogeneous devices such as GPUs, FPGAs and other architectures to manage execution. In this post, I will explain what it is, what can you do with it, and I will share some examples as well as my thoughts and experience after a few months of working with it.

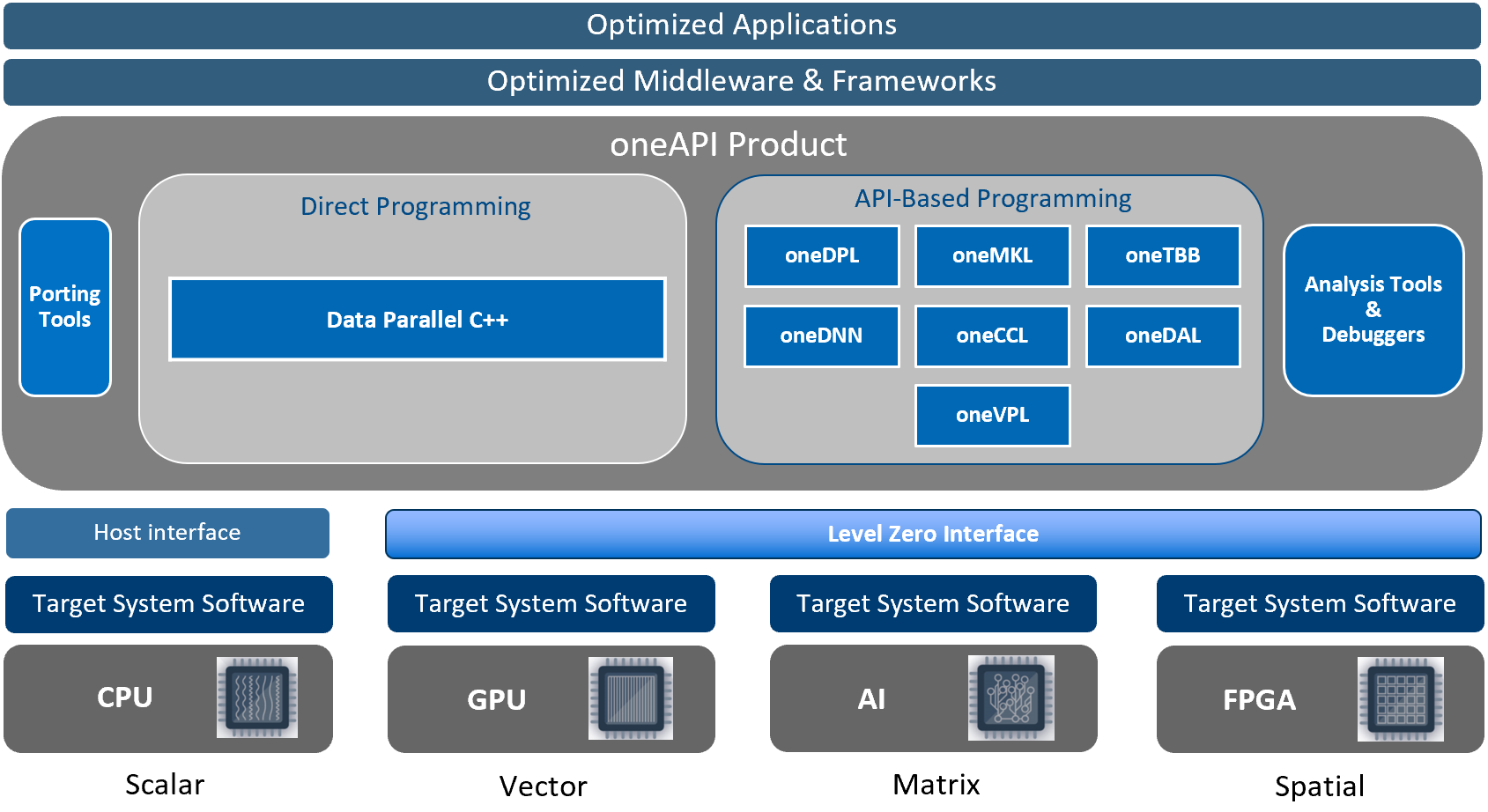

The Level-Zero API is shipped as part of the Intel oneAPI, which also includes a high-level parallel programming API that implements the SYCL standard (DPC++), as well as a set of libraries and toolkits for machine learning, deep learning, computer vision, etc.

The Level-Zero API is clearly influenced by OpenCL and Vulkan APIs and their respective programming models, with the flexibility that Level-Zero can evolve independently and match with the latest Intel GPU architectures.

But, what makes Level-Zero distinctive from the existing frameworks, such as OpenCL? The Level-Zero API supports virtual functions, function pointers, unified memory, device partitioning, instrumentation and debugging as well as control of power management, control of frequency and hardware diagnostics, just to name a few. This level of control is very appealing for system programming, runtime systems and compilers, making heterogeneous hardware more programmable/accessible.

But, where does Level Zero fit in the Intel compute ecosystem? The following diagram (taken from the Level-Zero spec 1.1.2) shows a representation of the Intel oneAPI products and Level-Zero. At the bottom level, we can see different hardware types with the corresponding drivers (Target Software System). This means that for GPUs, FPGAs and AI architectures, we could potentially program them using the Level-Zero API. However, I must say that, although the spec includes FPGAs and AI architectures, the current Intel implementation (as of June 2021) does not include other hardware than Intel GPUs. On top of the Level-Zero API there is the oneAPI and the DPC++ (Data Parallel C++) programming framework and all toolkits. However, we can program directly in Level-Zero without having to code in DPC++ or use the toolkits. In this post, I will explain the basic principles and I will show you an example.

Image source: Intel Level Zero Spec 1.1.2: https://bit.ly/3yJIOUW

2 - Level-Zero Architecture from 10000 Feet

Level-Zero has similarities with OpenCL. Thus, If you already know OpenCL, the design of Level-Zero will sound very similar. If you are not familiarized with OpenCL, I believe the learning curve for Level-Zero is much higher than OpenCL, since it is lower level and very verbose.

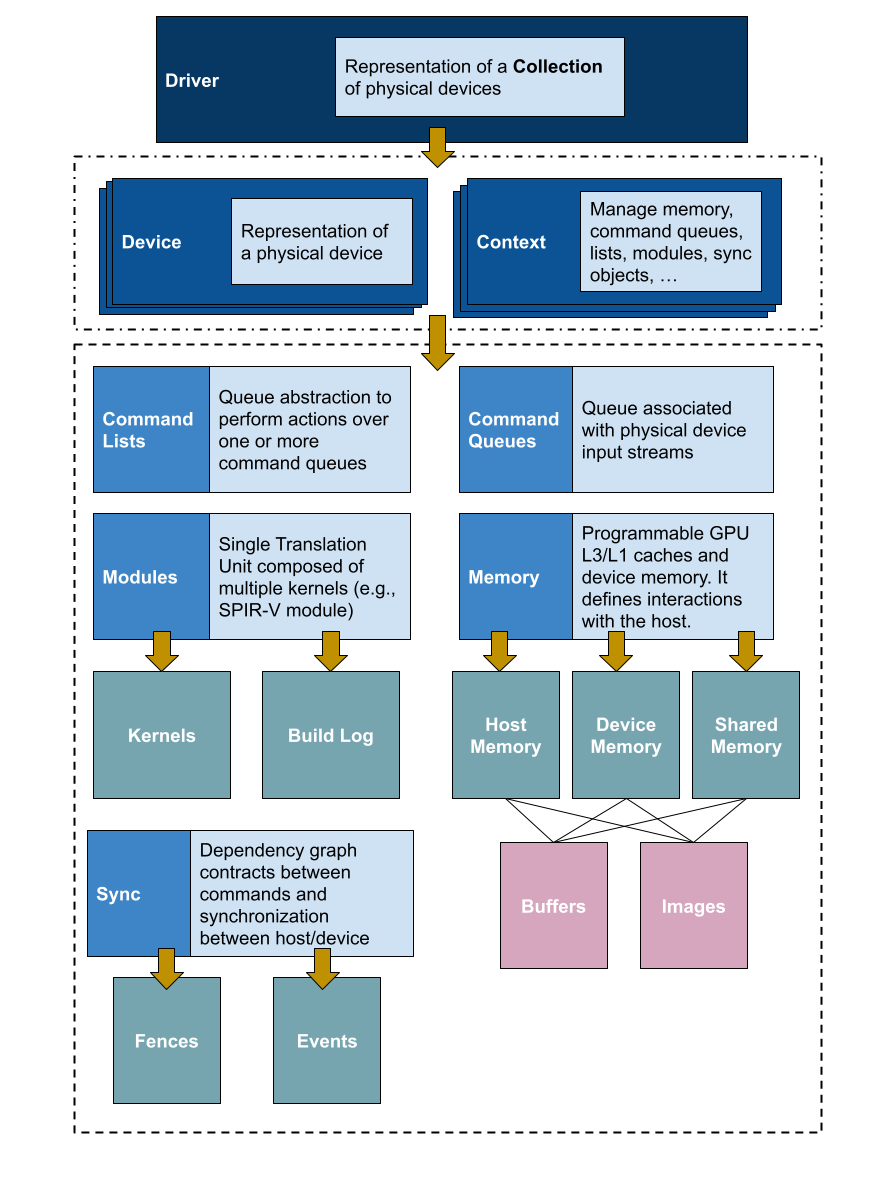

The following figure shows a high-level overview of the Level-Zero architecture, highlighting the main components and the main Level-Zero objects. At the top level, we find the Level-Zero driver, which is an object that represents a collection of physical devices (e.g., a collection of GPUs). Note that, more than one driver could be available in the system (similar to OpenCL). We can instantiate a driver object by invoking the zeDriverGet function.

Once a driver object is instantiated, we can create contexts and device objects. A context (similar to OpenCL) is an object that handles execution on heterogeneous devices, and is used for managing memory, commands, launch kernels, and performing synchronization.

A device object represents a physical device in the system. Through the device object, it is possible to query device properties, such as the memory available, the maximum number of threads, device name, etc.

It is important to highlight two basic data types in Level-Zero: handlers, and descriptors. Handlers represent the controller object (e.g., a context handler, a driver handler, etc). A descriptor is an object that is used to change behaviour of a particular handler, for example, passing flags, memory properties, synchronization properties, etc. For instance, to create a Level Zero context:

// descriptor

ze_context_desc_t contextDescription = {};

contextDescription.stype = ZE_STRUCTURE_TYPE_CONTEXT_DESC;

contextDescription.flags = 0;

// handler

ze_context_handle_t context;

zeContextCreate(driverHandle, &contextDescription, &context);

Using the device and context objects, we can create the rest of the objects needed for running a Level-Zero application, such as command queues and command lists, modules and kernels as well as creating buffers and image objects.

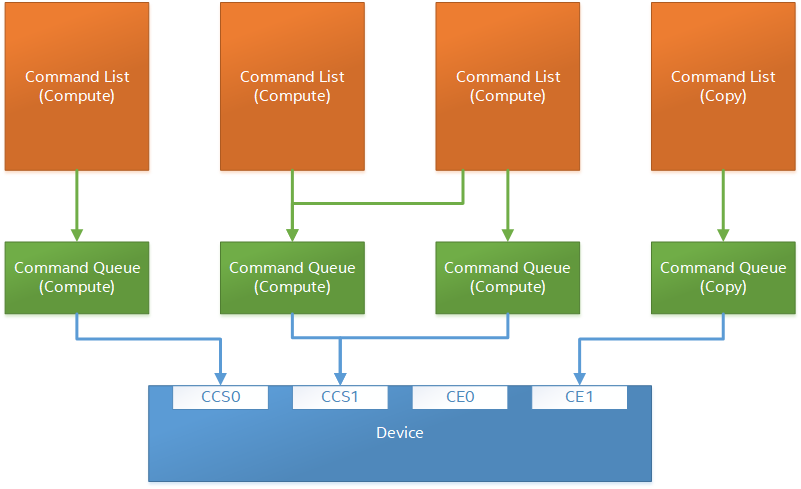

A command queue is defined as a “logical input stream to the device”, which in turn, is tied to a physical input stream. We can have multiple command queues associated with different input streams. A command list represents a list of actions to be performed over a command queue. It is possible to submit a command to different command queues through the same command list, or even to another command list.

The following diagram (taken from the Level-Zero 1.1.2 spec), shows the relationship between command lists and command queues. As we can see, there are two types of commands, one for compute and one for copies. Command lists can submit commands to different command queues. Command queues represent lower-level abstraction closer to the physical device. There is also a special type of command queue, called a low-latency command queue that we can use and avoid programming multiple command lists. Please, note that this is a high-level description, and for more detailed information, refer to the spec.

Image credit: Intel Level Zero Spec: https://bit.ly/3yJIOUW

With the context and the device objects, we can also reserve memory by allocating explicit buffers on device memory, host memory and/or shared memory, as well as by creating explicit images (multi-dimensional and user-defined memory).

Level-Zero can also dispatch SPIR-V kernels for computing. To do so, Level-Zero provides functions to build a SPIR-V module and create the kernel objects needed for the kernel dispatch. I’ll show an example in the next section.

Synchronization is also an important part of Level-Zero applications. There are two types of objects: events and fences. The use of these objects allows developers to insert barriers and fine-tune the dependencies between commands within command lists and command queues. These concepts are very similar to OpenCL as well.

Now that we have seen a high-level overview of the Level-Zero architecture, I will show you a simple example: dispatching a SPIR-V kernel for running matrix multiplication on the Integrated HD Graphics using shared memory. Existing? Let’s do this.

3 - Example: Dispatching a SPIR-V Kernel for Matrix Multiplication and Shared Memory

A) Download Level-Zero and build the project

What do we need to run Level-Zero applications?: a) Driver support: https://github.com/intel/compute-runtime/releases/ b) Level-Zero Loader (see instructions below)

To build the loader and the dynamic library of Level Zero, clone the project:

git clone https://github.com/oneapi-src/level-zero

And then:

mkdir build

cd build

cmake ..

cmake --build . --config Release

Note: I am using CentOS 7.9. If you are using any Linux distro, the build process is the same. We only need to be sure to use GCC >= 9.0. Therefore, in my case:

scl enable devtoolset-9 bash

If you are using Windows, make sure you enable the Qspectre mitigation libraries from Visual Studio.

Then we need to update the PATH for the headers and dynamic libraries:

export CPLUS_INCLUDE_PATH=$LEVEL_ZERO_PATH/include:$CPLUS_INCLUDE_PATH

export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=$LEVEL_ZERO_PATH/build/lib:$LD_LIBRARY_PATH

Now we are ready to start coding!

B) Level-Zero Application for Matrix Multiplication

In this section, I am going to explain the most representative parts of a Level-Zero application using the matrix multiply as an example. My example is based on a test for Level-Zero available on the Intel compute-runtime driver. You can also find the whole source code of the matrix-multiply example on GitHub, in case you want to follow along and try.

First, we Initialize the driver and perform the device exploration:

// Initialization

VALIDATECALL(zeInit(ZE_INIT_FLAG_GPU_ONLY));

// Get the driver

uint32_t driverCount = 0;

VALIDATECALL(zeDriverGet(&driverCount, nullptr));

ze_driver_handle_t driverHandle;

VALIDATECALL(zeDriverGet(&driverCount, &driverHandle));

Note, we use the macro VALIDATECALL to check the status of each call:

#define VALIDATECALL(myZeCall) \

if (myZeCall != ZE_RESULT_SUCCESS){ \

std::cout << "Error at " \

<< #myZeCall << ": " \

<< __FUNCTION__ << ": " \

<< __LINE__ << std::endl; \

std::terminate(); \

}

You should ALWAYS check for errors. However, in this post, for simplicity, I will skip the error control.

Now we can create a Level-Zero context:

// Create the context

ze_context_desc_t contextDescription = {};

contextDescription.stype = ZE_STRUCTURE_TYPE_CONTEXT_DESC;

ze_context_handle_t context;

zeContextCreate(driverHandle, &contextDescription, &context);

The next step is to instantiate a device object. We first need to obtain the number of devices that a driver has, and then we can create a list of devices.

// Get the device

uint32_t deviceCount = 0;

zeDeviceGet(driverHandle, &deviceCount, nullptr);

ze_device_handle_t device;

zeDeviceGet(driverHandle, &deviceCount, &device);

At this point, we can print some basic information about the device:

ze_device_properties_t deviceProperties = {};

zeDeviceGetProperties(device, &deviceProperties);

std::cout << "Device : " << deviceProperties.name << "\n"

<< "Type : " << ((deviceProperties.type == ZE_DEVICE_TYPE_GPU) ? "GPU" : "FPGA") << "\n"

<< "Vendor ID: " << std::hex << deviceProperties.vendorId << std::dec << "\n";

If we run the application of what we have so far, we should get something similar to this:

Device : Intel(R) HD Graphics 630 [0x591b]

Type : GPU

Vendor ID: 8086

Up to this point, I would say everything is quite close to the OpenCL API. Now we create the command queues and command lists. As I mentioned in the previous Section, here things differ.

To create a command queue, first, we need to check the command queues available on the device and attach an index of the command queue to the command queue and command list descriptor. In this way, we can map and “link” a command list to a command queue. Remember that command queues represent a low-level sequence of commands closely attached to a device, while a command list represents an abstract object regarding which command queue it can be submitted.

// Query number of groups:

uint32_t numQueueGroups = 0;

zeDeviceGetCommandQueueGroupProperties(device, &numQueueGroups, nullptr);

// throw exception if numGroups == 0

// …

std::vector<ze_command_queue_group_properties_t> queueProperties(numQueueGroups);

zeDeviceGetCommandQueueGroupProperties(device,

&numQueueGroups,

queueProperties.data());

ze_command_queue_handle_t cmdQueue;

ze_command_queue_desc_t cmdQueueDesc = {};

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < numQueueGroups; i++) {

if (queueProperties[i].flags & ZE_COMMAND_QUEUE_GROUP_PROPERTY_FLAG_COMPUTE) {

cmdQueueDesc.ordinal = i;

}

}

// Create a command queue

cmdQueueDesc.index = 0;

cmdQueueDesc.mode = ZE_COMMAND_QUEUE_MODE_ASYNCHRONOUS;

zeCommandQueueCreate(context, device, &cmdQueueDesc, &cmdQueue);

// Create a command list

ze_command_list_handle_t cmdList;

ze_command_list_desc_t cmdListDesc = {};

cmdListDesc.commandQueueGroupOrdinal = cmdQueueDesc.ordinal;

zeCommandListCreate(context, device, &cmdListDesc, &cmdList);

Now we can allocate memory using the shared memory malloc calls for Level-Zero. What we want is to allocate three matrices (a, b and c). For simplicity, we will use 1D representation and we will adjust indexing to access columns and rows appropriately. Since we want to use shared memory, Level Zero provides two memory descriptors that define how memory will be accessed from the host and device sides.

// Create two buffers

const uint32_t items = 1024;

constexpr size_t allocSize = items * items * sizeof(int);

ze_device_mem_alloc_desc_t memAllocDesc;

memAllocDesc.flags = ZE_DEVICE_MEM_ALLOC_FLAG_BIAS_UNCACHED;

memAllocDesc.ordinal = 0;

ze_host_mem_alloc_desc_t hostDesc;

hostDesc.flags = ZE_HOST_MEM_ALLOC_FLAG_BIAS_UNCACHED;

We can now do the malloc for matrix A, B and C:

void *sharedA = nullptr;

zeMemAllocShared(context,

&memAllocDesc,

&hostDesc,

allocSize,

1,

device,

&sharedA));

How we can access the buffer on the host side:

memset(sharedA, val, allocSize);

We do the same for matrices B and C:

void *sharedB = nullptr;

zeMemAllocShared(context, &memAllocDesc, &hostDesc,

allocSize, 1, device, &sharedB));

void *dstResult = nullptr;

zeMemAllocShared(context, &memAllocDesc, &hostDesc,

allocSize, 1, device, &dstResult);

Now it is time to create a module and build a SPIR-V kernel. Before going into the details to build a SPIR-V module using Level-Zero, let’s have a look at the kernel. We can compile an OpenCL kernel into SPIR-V using CLANG and LLVM.

__kernel void mxm(__global int* a, __global int* b, __global int *c, const int n) {

uint idx = get_global_id(0);

uint jdx = get_global_id(1);

int sum = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < n; k++) {

sum += a[idx * n + k] * b[k * n + jdx];

}

c[idx * n + jdx] = sum;

}

To compile this kernel to SPIR-V, we can use the following commands: notice that this assumes you have installed LLVM. In my case, I am using the Intel/LLVM fork.

$ clang -cc1 -triple spir matrixMultiply.cl -O2 -finclude-default-header -emit-llvm-bc -o matrixMultiply.bc

$ llvm-spirv matrixMultiply.bc -o matrixMultiply.spv

Now that we have the SPIR-V finary file built, these are the main calls to compile a SPIR-V kernel using Level-Zero:

std::unique_ptr<char[]> spirvInput(new char[length]);

file.read(spirvInput.get(), length);

ze_module_desc_t moduleDesc = {};

ze_module_build_log_handle_t buildLog;

moduleDesc.format = ZE_MODULE_FORMAT_IL_SPIRV; // <<< USE SPIR-V

moduleDesc.pInputModule = reinterpret_cast

<const uint8_t*>(spirvInput.get());

moduleDesc.inputSize = length;

moduleDesc.pBuildFlags = "";

auto status = zeModuleCreate(context, device, &moduleDesc, &module, &buildLog);

If there are any errors during the SPIR-V module creation, we can inspect the buildLog object. For details, please see the code on GitHub. Let’s now create the kernel object. This is a very similar process for OpenCL.

ze_kernel_desc_t kernelDesc = {};

kernelDesc.pKernelName = "mxm"; // Name of the Kernel.

zeKernelCreate(module, &kernelDesc, &kernel);

Now we are ready to dispatch the kernel. To do so, we need to setup the number of threads to deploy and the number of blocks. Note that we can first suggest to Level-Zero the number of threads to deploy for a specific kernel, and then set the threads based on the suggestions:

uint32_t groupSizeX = 32u;

uint32_t groupSizeY = 32u;

uint32_t groupSizeZ = 1u;

zeKernelSuggestGroupSize(kernel, items, items, 1U, &groupSizeX, &groupSizeY, &groupSizeZ));

zeKernelSetGroupSize(kernel, groupSizeX, groupSizeY, groupSizeZ));

Here you might notice that the block size we choose is not the one that is finally setup. The Level-Zero driver might choose better values. For example, in my case, even though I suggest 32x32 block sizes, the driver sets 256x1. By changing these values, you might see how performance drops, or increases. For example, if I choose 32x1, I get 10x over the C++ sequential code. But if I choose 256x1, I get 14x. Feel free to experiment with these values, but from my experience, Level-Zero will give you a good block size.

As follows, we set up the arguments to the kernel and we launch it from the command list.

// Push arguments

zeKernelSetArgumentValue(kernel, 0, sizeof(sharedA), &sharedA);

zeKernelSetArgumentValue(kernel, 1, sizeof(sharedB), &sharedB);

zeKernelSetArgumentValue(kernel, 2, sizeof(dstResult), &dstResult);

zeKernelSetArgumentValue(kernel, 3, sizeof(int), &items);

// Kernel thread-dispatch

ze_group_count_t dispatch;

dispatch.groupCountX = items / groupSizeX;

dispatch.groupCountY = items / groupSizeY;

dispatch.groupCountZ = 1;

// Launch kernel on the GPU

zeCommandListAppendLaunchKernel(cmdList, kernel, &dispatch, nullptr, 0, nullptr);

Note that we haven’t performed explicit data transfers between host and device. This is because we are using shared memory. Therefore, there is no need to perform data transfers before the kernel launch.

Since the kernel dispatch is a non-blocking call, to complete the execution of commands within a command list, we need to close the list and force execution over the command queue:

// Close list abd submit for execution

zeCommandListClose(cmdList));

zeCommandQueueExecuteCommandLists(cmdQueue, 1, &cmdList, nullptr);

zeCommandQueueSynchronize(cmdQueue, std::numeric_limits<uint64_t>::max());

Done! Now we should have the results available on the host side (shared memory).

If we run the application, by default is running 1024x1024 matrix multiplication, we will get something similar to this:

$ ./mxm

Device : Intel(R) HD Graphics 630 [0x591b]

Type : GPU

Vendor ID: 8086

#Queue Groups: 1

Group X: 256

Group Y: 1

GPU Kernel = 463028562 [ns]

SEQ Kernel = 6651558420 [ns]

Speedup = 14x

Matrix Multiply validation PASSED

What we have done with this example is to explain the main parts of a Level-Zero application and to dispatch a SPIR-V kernel using shared memory. You can view the whole source code on GitHub.

4 - What do I currently miss from Level-Zero?

I think Level-Zero is a great initiative, and I do love that it is open. I also appreciate that the main contributors of the project are open for suggestions and discussions on GitHub (at least this is my experience with them).

Having said that, at the point of writing this post (June 2021), I noticed a few things that, from my point of view, can be improved. Hopefully, some of them (if not all) will be solved/supported in future releases.

→ Just a disclaimer before I jump into some items: note that, since Level-Zero is open-source, the following “issues” can be provided by the community, including myself ;-) . This is just to point out a few things that I have found along the way.

What I miss in Level-Zero is, first of all, to include more documented examples, especially when using events, barriers, timers, etc. I know Level-Zero includes a suite of tests, and many of the utilities can be found there. However, I miss something similar to oneAPI examples but for Level-Zero. With these examples, it will be good to be able to easily evaluate performance and show comparisons against OpenCL (e.g., OpenCL command queues vs Level-Zero low-latency command lists).

I also miss a “conversion-table” from developers coming from OpenCL/CUDA. Actually, I must say that in the spec, there is extensive documentation for each function in Level-Zero, and it usually refers to the equivalent function (if it exists) for OpenCL. However, I think it will also be helpful if there is an equivalence table for the most common functions in a new section in the Level-Zero spec. I do believe this will help the adoption of this new technology.

From a more technical side, I think developers and newcomers to this technology will appreciate an introduction to the pNext field contained in most of the description data structures in Level-Zero. From my understanding, this field allows developers to extend properties by using different descriptor C-structs. However, I miss a use-case (full example/s) that showcases the potential of this and a compatibility table, meaning, which ones can I extend? And because extensions will influence, quite likely, performance, is there any suitable set of extensions that allows developers to increase performance for a particular domain of applications?

Besides, I miss better error control. For example, if developers accidentally miss resetting an already Level-Zero closed command list, Level-Zero does not complain when invoking consecutive calls with the closed-list. However, we get the wrong results because no commands will be executed (and with no warnings about it). In my opinion, this is very error-prone, and, indeed, it has happened to me several times. Therefore, currently, developers need to be very extra careful not to forget to reset command lists.

5 - Conclusions

Level-Zero is a low-level, close to bare-metal API developed by Intel and shipped as part of the oneAPI toolkits. This new API allows developers to fine-control the application for heterogeneous hardware, especially for GPUs, allowing the use of virtual functions, function pointers, efficient and fine-tune memory management, or even control the power and firmware.

This post has shown a high-level introduction to the Intel Level-Zero API. It first showed a general introduction and an overview of the programming model. Then it showed a step by step example for dispatching a SPIR-V kernel on Intel HD graphics using Level-Zero. Finally, it highlighted some remarks about what I consider missing in Level-Zero, and which parts I would like to see the community contributing to this project.

I do believe the Level-Zero API is a great way to access heterogeneous hardware, controlled by runtimes, OS and system software, giving developers the possibility of fine-tuning applications to maximise resource utilization and portability of high-level applications when running on heterogeneous hardware.

Acks

I would like to thank Athanasios Stratikopoulos for the constructive feedback on this article.