Overall Performance of Unified Shared Memory Types with Level Zero on Intel Integrated GPUs

Published:

Key Takeaways

- Shared memory buffers in Level Zero are buffers allocated by the host that are accessible from the host and the device.

- The device can migrate host memory to device memory in order to increase performance.

- Using shared memory for non-heavy computing kernels can lead to a performance of up to 3.5x compared to the device and/or host memory on Intel integrated GPUs.

- Shared memory buffers offer the same performance (end-to-end) compared to device and host buffers when running highly compute-intensive applications

- Using host-only memory performs the same as using shared memory allocation types on Intel integrated Graphics.

Integrated GPUs, such as Intel HD graphics, share the memory with the main CPU, offering a common view of the main memory. This means that, potentially, we could use buffer pointers allocated on the host side on the GPU, and, therefore, save the data transfer time (e.g., a copy from host memory to device memory, which can be expensive in many cases). In Level Zero, this is called Unified Shared Memory (USM). However, does share memory really impact performance if we measure end-to-end applications on GPUs? In this post, we try to answer this question.

Unified Shared Memory Allocation Types

Before digging into Level Zero shared memory, let’s take a look at the different allocation types of Unified Shared Memory that are available in Level Zero.

There are three main types of allocations:

- Host Allocation: host buffer allocation is owned by the host and accessible to the host and device. Note that, although the device can access the same host pointer, there is no data migration between host and device. Therefore, when the GPU kernel needs access to the host pointer, it will access to host memory.

- Device Allocation: buffer allocation on device memory. This buffer cannot be accessed from the host directly, and it needs to transfer data from the host to device memory explicitly. Discrete GPUs, for example, usually provide much higher memory bandwidth compared to CPUs. By allocating buffers in device memory, the GPU kernel can offer higher throughput if data are accessed frequently.

- Shared Allocation: buffers that are shared across host and device. In contrast to host allocation, buffers allocated with shared memory can be migrated between host and device. This is done transparently by the GPU driver (the Level Zero driver in this case). The advantage of this model is that developers can avoid explicit copies between host and device. Therefore, is easier to read and maintain the code, and less prone to errors.

Study of Different Types of USM Allocators

We provide two use cases: one GPU kernel that performs a data copy (no computation) and another kernel that performs a compute-intensive application (we choose the canonical example of matrix multiplication).

The code to reproduce the following experiments is available on GitHub.

Additionally, all numbers reported are taken after a warm-up phase (last iteration of 10 runs). Note that page migration is done for shared memory when running multiple times. However, similar results can be found even including the first iteration compared to other types of allocators. The reported times show end-to-end (which includes copy-in, kernel and copy-out). Since the GPU kernel is the same for all versions, we want to measure the overall impact of each buffer type in the total time. The total time was obtained using Level Zero timers.

The experiments were executed on two hardware setups:

- A laptop Setup using an Intel Core i9-10885H CPU, which contains an Intel CometLake-H GT2 GPU, which runs Fedora 34 with the OpenCL 21.38.21026 driver.

- A work-station setup with more recent hardware, which runs Ubuntu 22.04 LTS on an i7-12700K CPU with an AlderLake-S GT1 GPU. The OpenCL driver installed is the 22.20.23198.

a) Low compute-intensive application

In this experiment, we want to highlight the overheads of different data transfers and memory allocators by minimizing the compute part. We execute a GPU kernel that performs a copy and one operation to store in a second buffer. We execute the kernel for a range of different input sizes (ranging from 64MB to 4GB).

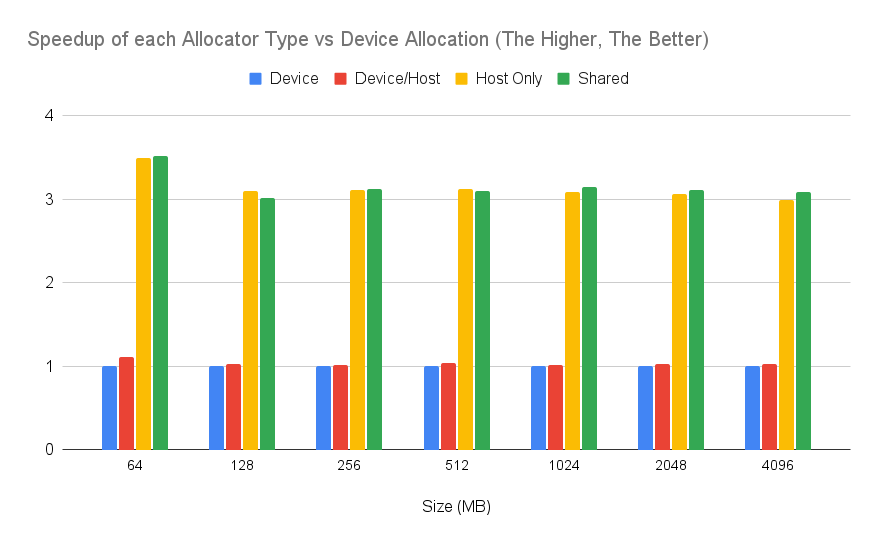

The following plot shows the speedup on the laptop configuration (Intel Core i9-10885H CPU) of end-to-end applications running with different level zero allocator types. The baseline is device allocation (the first bar of each group), while the second bar shows the allocation of host memory combined with device memory. This means that memory is allocated on the host, and then transferred to a device buffer. We checked this scenario to mimic behaviour for managed runtime systems (e.g., Java, in which objects and user data reside on the Java heap, and then it is copied to accelerators using device memory). The third bar shows the overall speedup over device allocation when using host memory only. The last bar shows the speedup using buffers allocated with shared memory. Therefore, shared and host-only implementations do not perform any copies between host and device.

Figure 1: Performance of each allocator type compared to device type running on a laptop configuration. The higher, the better.

From Figure 1, we see that using shared memory and host memory leads to the best performance overall (~3.5x) compared to the device memory. Interestingly, the combined host/device buffer strategy (second bar) performs the same (even a bit faster) than device only memory allocation. Another interesting finding is that the execution with host-only buffers (third bar) performs roughly the same as running with shared memory. A possible insight to analyse this behaviour would be to study if the buffer migration occurs when using the shared memory type.

Similar patterns can be found when running on a workstation with more recent drivers:

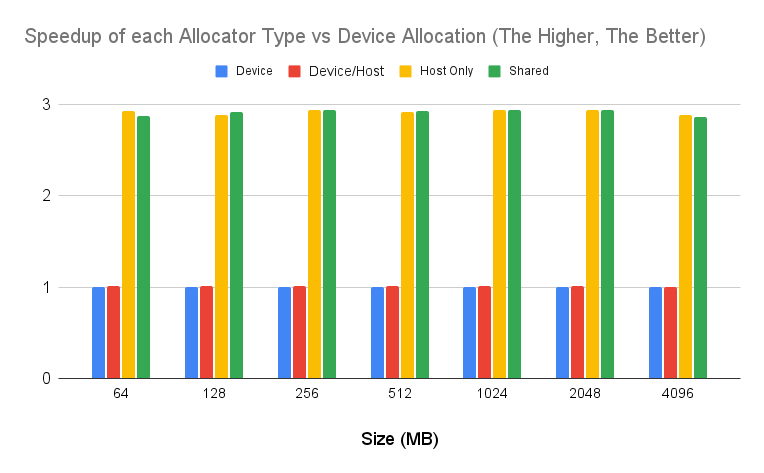

Figure 2: Performance of each allocator type compared to device type running on a workstation. The higher, the better.

Running on the workstation with a more modern GPU, we also see that host only memory and shared memory achieves a faster execution time compared to device memory. This is due to the device and the combined device/host performing a buffer copy from one buffer to another.

The takeaway from this experiment is that for shared memory systems, such as an Intel integrated GPU that shares memory with the main CPU, running either with shared and/or host-only memory can increase performance.

b) High-intensive compute application

Similarly, we conduct the experiment for a compute-intensive application.

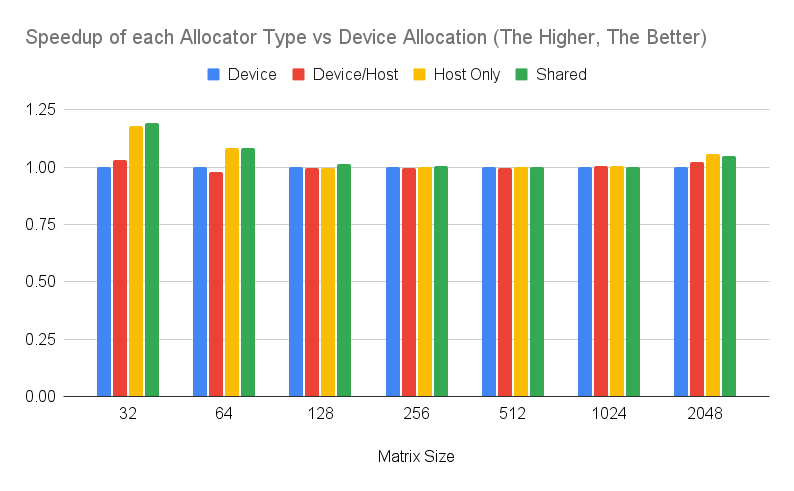

The following Figure shows the performance numbers running on the laptop setup (Intel Core i9-10885H CPU). We see that there is not much difference between allocators on a shared memory system between the GPU and the CPU. This is due to data migration overheads being shifted by the actual computation. So in this example, the bottleneck is not the data transfer, but the computation of the kernel. While there are some minor differences I would not conclude they are significant (running on the desktop CPU along with other background applications).

Figure 3: Performance of each allocator type running a compute-intensive application compared to device type on a laptop configuration. The higher, the better.

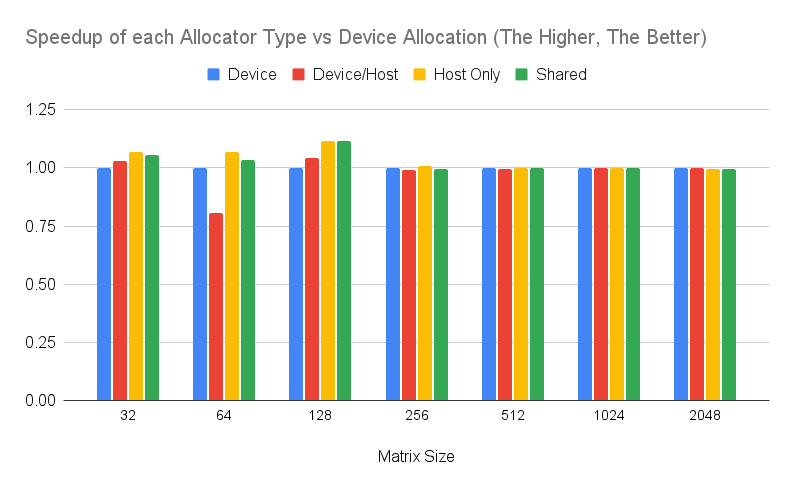

Again, a similar pattern can be found when running on a more recent system. The following Figure shows the performance numbers when running on the workstation (i7-12700K).

Figure 4: Performance of each allocator type running a compute-intensive application compared to device type on a workstation. The higher, the better.

What we take from this experiment is that, when running compute-intensive applications on a shared memory system, the decision about which buffer allocator to use is not that relevant compared to improving the GPU kernel.

Conclusions

This post has explored the performance of unified shared memory (USM) within Level Zero. We show the different types of USM can a performance evaluation comparing each of them.

As a takeaway, if we use a shared memory GPU system, a good choice would be to use shared memory buffers and/or host-only memory. This will give us better performance compared to other approaches for small input sizes, and with on-par performance compared to the best allocator (device memory) for compute-intensive applications.

Of course, this story might change when running on discrete GPUs (e.g., the upcoming Intel XE Discrete GPUs).

Additionally, if you have any comments or suggestions feel free to contact me or interact in the following thread for this entry post:

https://github.com/jjfumero/jjfumero.github.io/discussions/7

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Steve Dohrmann and Peng Tu from Intel and Christos Kotselidis and Athanasios Stratikopulos from The University of Manchester for the constructive feedback and fruitful debates on this post.